TOLEDO, Ohio — It came with little warning. Weather forecasters started talking about the chance of a unprecedented storm about 18 days before it actually became a reality. Two massive winter storms of intense low pressure were about to collide over Ohio and much of the Midwest. But, Toledo appeared to be near the bull's-eye.

By dawn on Thursday, Jan. 26, 1978, the worst fears were coming to fruition. The overnight rain that left the streets of Toledo were then a sheet of ice as the temperature fell. And as they fell below freezing, the snow came and then the wind.

By 6 a.m., streets were already snow-clogged and nothing was moving. The city of Toledo and all of the counties around Lucas were in a death grip of winter. Blizzard winds hammered the area and drivers that had tried to venture out found themselves stranded on streets that even the big plows couldn't bully through.

TARTA buses shut down, schools, offices, most businesses and even emergency medical service were affected. Snowmobilers and people with four-wheel drive vehicles were being summoned to help the Red Cross, the fire departments and other agencies that needed to transport people, supplies and even pregnant women in labor. At least three women in the area had to be taken to hospitals during the course of the storm to give birth. One woman in Oregon was taken by snowmobile to St. Charles.

Electricity was out for thousands in the immediate Toledo area as trees had toppled over onto limbs and many lines came down under the weight of ice and snow. Toledo Edison tried to keep crews on the road in the blinding snow as they worked day and night to restore power. Temperatures had plummeted to the single digits and many homes were dependent on the electricity to keep the furnaces running.

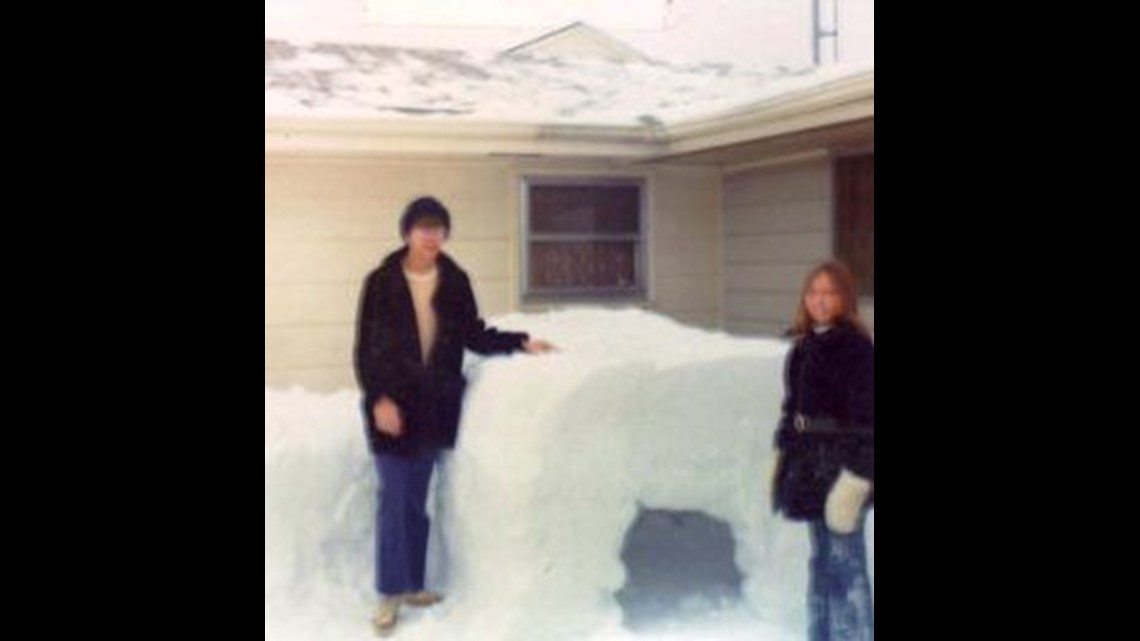

By Friday, Jan. 27, 1978, the situation had not gotten any better. It had deteriorated to the level of life and death for those who were cold and stranded. President Jimmy Carter deployed the 5th Army from Ft. Bragg to fly into Toledo with about 50 heavy pieces of equipment and hundreds of troops to operate them to open roads and get life back to some semblance of normal. It would take days. Rural areas around the city were the hardest hit and in the most dire situations as the blizzard winds pushed drifts higher than 10 feet in some places, trapping people inside their homes. Wood, Hancock and Ottawa counties were priorities for the Army battalions that worked round the clock to move the snow from the country roads and highways.

For some, the help was not enough. Several people died from exposure. Across Ohio, more than 50 people died in the storm; in Michigan, more than 70 perished.

Thousands of travelers got to spend time in Toledo they hadn't planed for, as the Greyhound and Amtrak station filled with stranded passengers who were waiting out the emergency and hoping to get on their way. All hotels were booked and special shelters were set up in Toledo and elsewhere for the large number of highway travelers and truckers who were stuck until the roads were made passable again.

By Monday, Jan. 30, 1978, the area was starting to regain its equilibrium. Stores and businesses began to reopen, power was getting restored, abandoned vehicles were moved off the streets and most of the major roadways were passable, albeit slow going. The airport reopened and buses and trains began moving.

For Toledo Mayor Doug DeGood, who had been stranded on the East Coast by a storm, it meant that he was able to get back to the city and to take charge of the city's challenge of cleanup. Digging out, however, took days - weeks in some areas - as winter was far from over, and the winds and snow would blow again.

But never, not that winter or the next 40, would any storm ever rival the Great Blizzard of 1978.