COVID-19: Behind the numbers in Ohio

In nearly five months, a pandemic has reshaped our world. Data show the journey we have traveled.

On March 9, Ohio declared a state of emergency after announcing its first three COVID-19 cases.

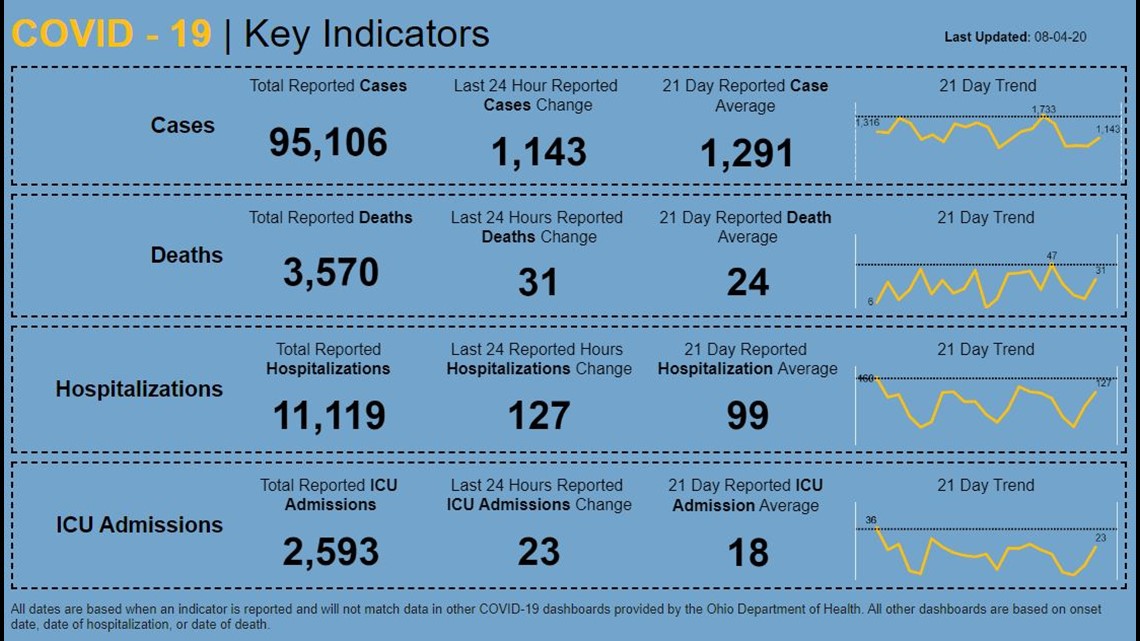

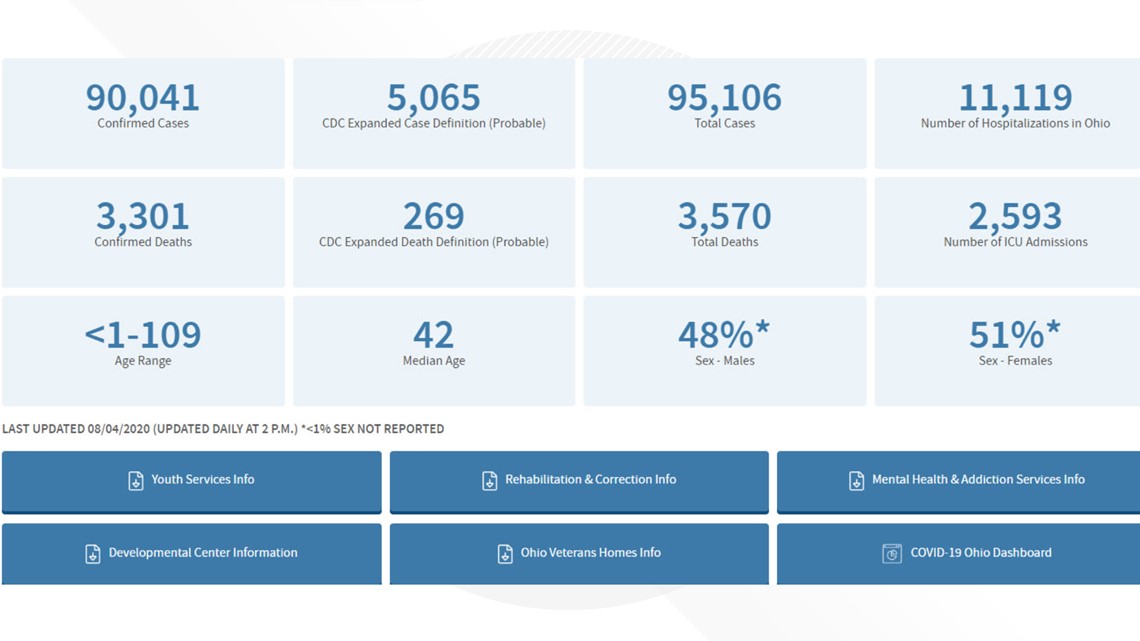

In nearly five months, the state has now reported 95,106 cases (90,041 confirmed) and 3,570 deaths (3,301 confirmed).

As the pandemic has worn on, WTOL has gained additional access to state data - sometimes voluntarily, sometimes through public records requests.

It has been my goal - and also WTOL's - to present "Facts, Not Fear." Sometimes, however, it has been hard not to have a little fear when presented with the facts.

But here is a look - through the numbers - at where we have been and where we are currently.

Cases Cases

Cases have been the most vexing number for people who have been analyzing the data. They are the headliners, particularly when there is a large spike, or even a large drop.

In Ohio, the numbers have been unreliable and inconsistent. In the beginning, the state was lumping all probable cases in with confirmed cases, meaning that a case could be declared even without a confirmed laboratory test. At this point, the state breaks cases down into confirmed and probable cases on its dashboard. The probable cases include those who are determined to have antibodies to the virus, along with other clinical symptoms. However, the state's daily announcement is still a combination of confirmed and probable cases.

Another issue I noticed early on was that numbers are almost always low on the weekend, as some tests and deaths are not reported until the beginning of the following week. For whatever reason, Monday is not typically the big day, but rather Tuesdays and Thursdays.

After meeting with one of the state health department's data collectors, it was decided to use seven-day averages to get a more accurate snapshot of where we are in the pandemic.

It seems hard to remember at this point, but the state was only averaging 381 cases a day in mid-June. Last week, that number was 1,345 cases per day.

The surge in cases began in late June and peaked last Thursday, when Ohio reported 1,730 cases. That spike mirrors what has happened across much of the United States. In mid-June, the U.S. was averaging fewer than 20,000 cases per day, an average that spiked to 70,000 last week. Like the rest of the country, Ohio's numbers have dropped in the last several days.

So what happened? A lot of people like to point to protests as the reason for the spike, but there have been few cases that contact tracers have tied to protests that roiled the country after George Floyd's death in late May. The clearer culprit is likely the July 4th weekend. Several outbreaks were traced to family get-togethers, bars, and house parties. With the incubation period, along with waiting period for test results, those infections would be identified around the time of our state - and national - surge in cases.

Last Thursday, Gov. Mike DeWine highlighted Lucas County as one of the areas of the state that was having large surges. Lucas County led the state in deaths throughout most of May as the virus ravaged nursing homes. But almost all of the local cases, certainly the deaths, were in those facilities. When Cleveland, Cincinnati, and Columbus began surging in late June and July, our area was only seeing a handful of daily cases.

However, that began changing in the last couple of weeks. The county has reported more than 1,200 cases in two weeks. Records requests from the county health department identified a funeral and multiple restaurants as hot spots for the virus. Contact tracers have identified nine restaurants with multiple cases. El Camino Real on West Sylvania has had seven customers or employees who have tested positive.

Testing Testing

But many viewers have rightfully pointed out that the surge in cases has coincided with a large increase in daily testing. In March and April, a person could only be tested if they had symptoms consistent with COVID-19. That is no longer the case. You can be tested at multiple locations, even without symptoms.

In mid-June, when the state was averaging fewer than 400 cases a day, Ohio was testing roughly 10,000 people a day. Last week, the number was closer to 25,000 a day. Logically it makes sense that more tests will detect more positives - even people who are asymptomatic. But the surge also saw an increase in the positivity rate. The World Health Organization wants this number to be below 5% for 14 days before reopening the community. The number means the percentage of people who are tested who actually test positive.

In April, the state average was 25%. But remember, people could only get the test with symptoms or a doctor's note. As testing became more accessible, the positivity rate dropped to 3.5% in mid-June, but it jumped to more than 7% in early July. The state was testing many more people (in late July, more than 50,000 tests were done in one day), but the people were testing positive at twice the rate of the month before. It was a clear indication of widespread community infection.

And the ramp-up in testing brought an unintended consequence - testing delays that likely increased community spread. At one point, people were getting tests returned in 48 hours. This would allow that person to go into quarantine and for contact tracers to quickly reach out to people possibly exposed to that person. But as labs began processing more tests, the delays became longer.

The average became a week. People reached out to me saying their wait had been as much as 10 days. To avoid infecting others, people who aren't feeling well, or even who took a test, should avoid others. But the delays made it almost impossible, and the Toledo-Lucas County Health Department reported that people were infecting others while waiting for their test results.

Deaths Deaths

People will always focus on the deaths, because that is, obviously, the worst outcome of a COVID-19 infection. But the state's counting of deaths, by its own admission, is not a good indicator of what's going on. In some cases, a death that is reported on Monday may have occurred weeks earlier.

And, at this point, it's not even clear that all of the people being counted as COVID deaths actually died from COVID-19. My investigative colleagues Phil Trexler and Rachel Polansky at our Cleveland sister station reported on the death of 37-year-old Richard Rose of Port Clinton. Rose was found dead in his home days after testing positive for the virus.

The coroner told responders to take the body directly to the funeral home, without an autopsy, or even blood draw or examination, that would typically be expected in the death of a 37-year-old. His death was ruled a COVID-related death. Coroners are operating under different guidelines, and some people are being declared a COVID death because they had COVID or, at least, had COVID symptoms.

More than 60 percent of the state's reported deaths have occurred in nursing homes, including several deaths of residents who were more than 100 years old. The median age for an Ohio COVID-19 death is now 80 years old. It will take years for medical experts to determine whether the death count was under or overcounted.

Hospitalizations Hospitalizations

I have intentionally spent most of my time focusing on hospitalizations. Those numbers deliver the most accurate snapshot of where we currently stand. They are based on Ohio Hospital Association daily surveys.

When we saw the virus rampage through Detroit in March and early April, emergency rooms and intensive care units were swamped by patients, making it more difficult to care for non-COVID-19 patients and COVID-19 patients alike.

What we began seeing the second week of July in Ohio was a big jump in new hospitalizations. This wasn't surprising because we know that roughly 15% of infections result in hospitalization, so the surge was going to create more hospitalizations. The week of July 17 saw a daily average of 106 new hospitalizations. We don't have data on how many are people being discharged daily, but we do know the daily hospital count for COVID patients, and that number reached a high of 1,144 patients on July 28.

I have continually requested data on hospital capacity, believing that the state would reach a crisis point when its hospitals became overwhelmed like Detroit was in March and like we are currently seeing in Florida and Texas.

Last week, the state finally produced those numbers. We were provided with hospitalization data going back to early March. What was really interesting is that when we had our first big surge in April, the hospital count for COVID-19 patients reached 1,103 on April 22. But there were only 12,079 non-COVID patients. Hospital capacity was close to 58%.

But the summer months historically result in more hospital patients. And this summer has seen a surge as people began having elective surgeries that they could not have in the spring. Even though the COVID-19 patient count was similar on July 28 to April 22, the number of available beds was much lower last week because of non-COVID-19 patients. There were 16,950 non-COVID patients on July 28. The capacity percentage was 70.

Case numbers will likely fluctuate over the next several months, but it will be crucial to keep COVID hospitalizations under control as we enter flu season.

Where are we now? Where are we now?

For the first time since the first week of July, Ohio's daily average has fallen below 1,000 cases (987), new hospitalizations are also at the lowest daily average in about a month (82).

There are people who are still resistant to masks, but Ohio mandated mask use on July 23. Next week's numbers should be a better indicator of how that mandate is affecting spread. But some of the lower numbers now being reported fall in the post-mask mandate window.

As far as hospitalizations, the current number of COVID-19 patients is still at 1,038. That number was 482 on June 20. On Monday, the state had 199 patients on ventilators, the most since the beginning of the pandemic.

Our hospital bed availability continues to be above 30 percent and 40 percent in the ICU, so those are good signs. Even though the state is at highs for ventilator use, it is still reporting that 73.5% of ventilators are available.

The state is nowhere near its early to mid-June numbers, but there are some positive signs that Ohio is keeping the outbreak to levels that can be handled by our hospital system.