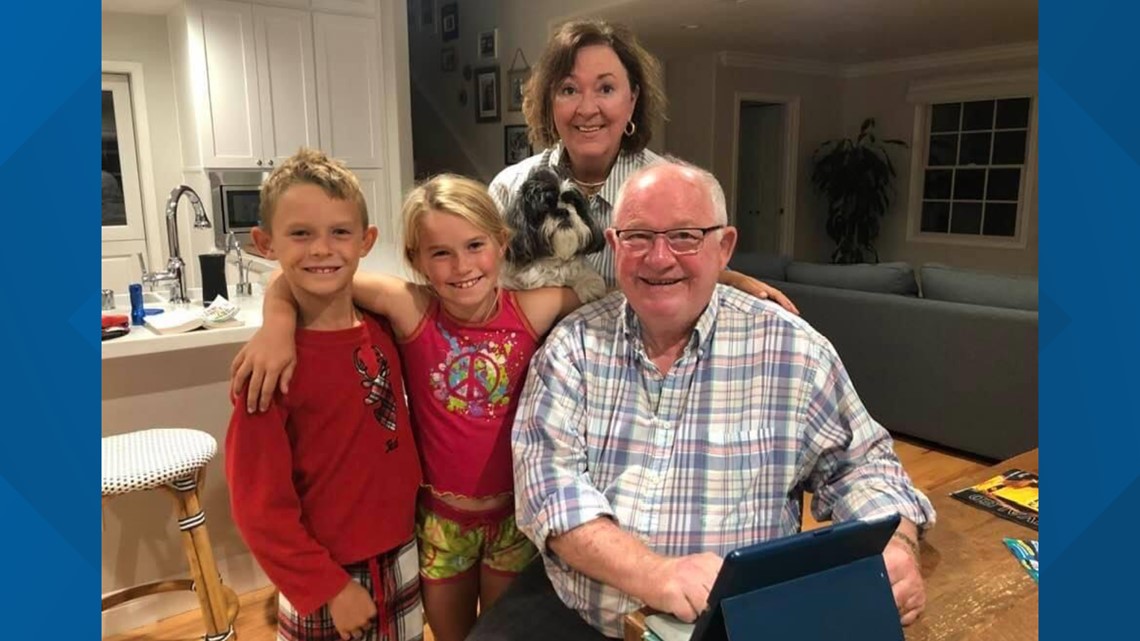

TOLEDO, Ohio — Mark Wagoner leans forward in his chair inside the Shumaker, Loop & Kendrick law offices on Jackson Street. He smiles, allowing his thoughts to drift back to a trip to Florida with his family as a 14-year-old.

The longtime lawyer played several sports while growing up in Ottawa Hills. His father, Mark Wagoner Sr., was a former star athlete at Shelby High School and Ohio Northern University. But at the time of that Florida trip, "Mick" Wagoner was an affable, 47-year-old, chain-smoking lawyer who would entertain his friends at the courthouse with dirty jokes.

"Somehow we ended up racing each other, and he beat me by a stride," Wagoner says. "After that, he went back, sat down, had a smile, but he really didn't say much. He would never race me again. But I think it was that great moment when you think you might just have a step on your dad, but really your dad has a step on you."

On March 18, Mick Wagoner, 76, died of COVID-19. The history books will eventually settle who was the first person to die from the disease in Ohio. If Wagoner wasn't the first, he was certainly one of the first. A year later, Ohio now has nearly 17,000 COVID deaths and close to 1 million people who have been infected.

Two months before Wagoner's death, hints of the approaching storm began to surface. A Jan. 8 headline in the New York Times read: "China identifies new virus causing pneumonialike illness."

Then about two weeks later: "First patient with Wuhan coronavirus is identified in the U.S."

By February, deaths linked to COVID were being reported in California and the state of Washington. A Feb. 29 Everett Herald (Washington) headline blared, "First U.S. death tied to new coronavirus reported in Kirkland."

And Wagoner was sickened after traveling.

"When he first started having symptoms of COVID, I said, how does Mick Wagoner from Toledo, Ohio, come down with a virus from China?" his son says.

Ohio Gov. Mike DeWine sounded the alarm on March 9, announcing the first three cases of COVID-19 and declaring a state of emergency.

Days later, the governor gathered the state's big-city mayors on a conference call and hammered home the storm that was about to sweep into the state. He told the mayors that they were now at war with an unseen enemy.

"It was spoken in very stark, very serious terms. I remember him saying that we might see things that resemble third world countries - triage, M.A.S.H. units in parking lot hospitals," Toledo Mayor Wade Kapszukiewicz says. "That moment was when I sat up and said, 'oh my goodness, this is worse than I thought it was.'"

Kapszukiewicz ended the call, then called his senior leadership.

"I told them we were going to be facing some dark months, that this wasn't something that was going to go away in weeks."

Then he called his wife and told her that their kids would probably be forced to learn remotely within days. "I distinctly remember telling her that this was a lot worse than we thought it was."

On March 22, the state took a step it had never taken before. Dr. Amy Acton, the health director, signed a stay-at-home order.

Store shelves emptied, students were forced to their laptops and families wondered what was to come.

VIRUS RAMPAGES THROUGH NURSING HOMES

Before the state even realized that the virus' primary target was the elderly, it had decimated Ohio's nursing homes - residents and staff.

During the early months of the pandemic, the nursing homes in Lucas County were hit particularly hard. When the state started reporting deaths in April for nursing homes, Lucas County led the state. While the county continues to slide down that ranking, Lucas County still had 264 deaths in its nursing homes as of this week.

RELATED: Most Lucas County nursing homes with COVID-19 cases have history of poor health inspections

"Nursing homes are a concern for us," Eric Zgodzinski, Lucas County health commissioner, said last spring. "We know once it gets in there, it's hard to stop."

And it became impossible for facilities around the state. As of this week, 6,602 deaths have taken place in Ohio nursing homes, roughly 40 percent of the state's totals.

PRISONERS TRAPPED BY VIRUS

There was another easy target for the virus - the state's prisons.

Once the virus was brought into the prison - via visitors, corrections officers, or new prisoners - it was nearly impossible for the facilities to stop the spread.

More than 11,600 staff and prisoners have been infected and 144 had died as of this week.

A local man, Nico Panthavon, was released from Marion Correctional Institute in April. In a video provided to WTOL, he is seen telling his family: "They just told me I tested positive for that coronavirus on the way out the door."

In a later interview, he described medical units set up in all areas of the prison, sick prisoners coughing throughout the night, and the constant fear of being infected.

"I watched a man fall down and break his teeth. They came in and just let him go. He fell down multiple times. He couldn't eat food. They told him to just drink water," he said.

FEAR GRIPS COMMUNITIES

As Ohio entered a lockdown last spring, fear gripped many as so little was known about the virus. Hand sanitizer, toilet paper, and sterilizing wipes flew off store shelves. Initially, reports were that the virus could live on surfaces for hours, even days, or that it could be transmitted through food.

Others refused to believe that it was any worse than the flu.

"This is not the flu. My head hurt, my hair hurt. I can't even express to people enough that they need to take this seriously," said Betsy Bunda, a Rossford woman who was infected on a vacation to Europe with her husband, Bob.

Communities began preliminary plans to build COVID units inside of arenas or convention centers. Dire predictions warned of hospitals being overrun. But by the beginning of summer, COVID patients in Ohio had dropped to 513 and the state was only seeing hundreds of confirmed patients a day.

But every time residents let down their guards for holidays or at family get-togethers, the virus roared back. In the weeks after the 4th of July, hospitals numbers and cases swelled to more than 1,000 a day. The same patterns followed after Labor Day, Thanksgiving, and Christmas. By the beginning of December, there were more than 5,000 COVID patients in the state and cases were routinely topping 10,000 a day.

By the beginning of March, 2021, the coronavirus had infected 115 million people around the world. 2.5 million died from COVID-19. Nearly 1 million Ohioans tested positive. More than 17,000 died.

SCIENCE STEPS UP

During one of the world's darkest periods, science shined brightly. After China released the virus' genetic sequence early last year, scientists went to work on defeating it. Within nine months of the virus spreading to the United States, Pfizer and Moderna had produced the first vaccines approved for use by the FDA.

Their vaccines utilized messenger RNA technology, which had not previously been approved for mass distribution. But it was the quickest route to a protective shield. Genetic coding was injected into the body while inside a protective fatty bubble. That coding told the body to produce the spiked protein that gives coronavirus its name. It is the only part of SARS-Cov-2 (which causes COVID-19) that the body produces, rendering it completely harmless. Once the body encounters it, it learns to defeat it and remembers it in case it encounters the actual virus.

Scientists initially hoped for a vaccine that would prove at least 50 percent effective. But in trials, the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines were 95 percent effective.

By mid-December, the Pfizer vaccines were being flown out of Grand Rapids. And early this month, a third vaccine, Johnson & Johnson, began rolling out of Kentucky. Johnson & Johnson, tested in many different countries and against some variants, has a lower efficacy rate, but it is a single shot and does not need to be stored at super cold temperatures.

RELATED: VERIFY: Explaining how the Johnson & Johnson vaccine works and what makes it different from others

A REASON TO HOPE

By February, case numbers and hospitalizations were in a free fall. By March, mass vaccination clinics were opened across the country, Pfizer and Moderna had refined their production capabilities, and Johnson and Johnson and Merck agreed to work together to speed production. On March 3, the United States surpassed an average of 2 million vaccines a day for the first time.

Ohioans and Americans held their breath, wondering if it is was possible to begin dreaming of normalcy.

"I can envision a summer with no masks, or limited masks, where going to Mud Hens game, getting ready to go to the Walleye, the downtown concert series, Marathon Classic, the Solheim Cup," Kapszukiewicz says.

More than 650 Lucas County residents have died from the virus in the past year. Thousands of families have been forced to wage their own battle with the virus. But, economically, Toledo has been able to prevent its economy from being decimated.

"I think the story of Toledo is our resilience, our grittiness, and how we've been able to battle through. Not just to keep our nose above water, but to really come out of this in a strong position," Kapszukiewicz says. "I feel very bullish on where we are going to be six months from now."

While some plan their future memories, others draw on remembrances of family and friends they have lost.

In his Toledo law office, Mark Wagoner smiles as he recalls a trip to Florida as a 14-year-old. A cocky athlete, he challenged his chain-smoking, 47-year-old dad to a race.

"He beat me by a stride. After that, he went back, sat down, had a smile, didn't really say much, but he would never race me again. But I think it was that great moment when you think you just might have a step on your dad, but your dad has a step on you."