TOLEDO, Ohio — Northwest Ohio historians and cemetery curators are working together to bring a name back to life and honor a legacy.

The Forest Cemetery in north Toledo is currently asking for donations to add an individual's name to their family headstone.

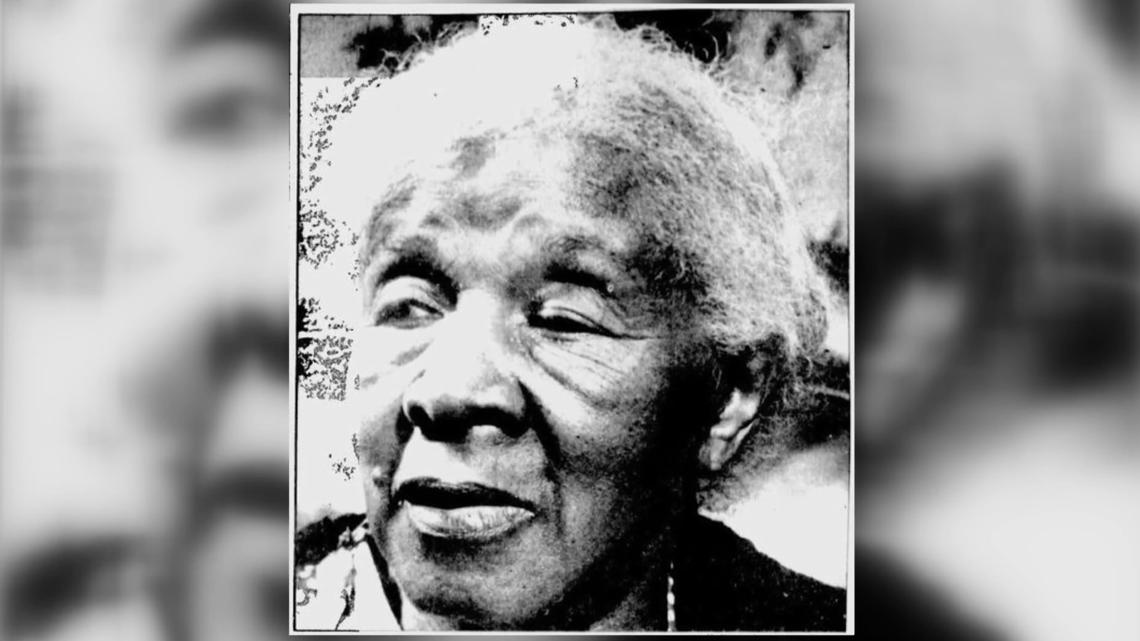

In 1856, Julia Ward was born to enslaved parents in Kentucky. Nearly 170 years later, local historians are working to add Julia's name to her family's gravestone, where her name has been absent since her death.

Julia Ward escaped enslavement before the American Civil War with her mother by crossing the Ohio River into Ohio along the underground railroad, where she eventually escaped to Canada by way of Detroit.

She returned to Ohio in 1869, where she later married Albert King in 1875. Together, the Kings lived in Toledo where they had one daughter named Doris.

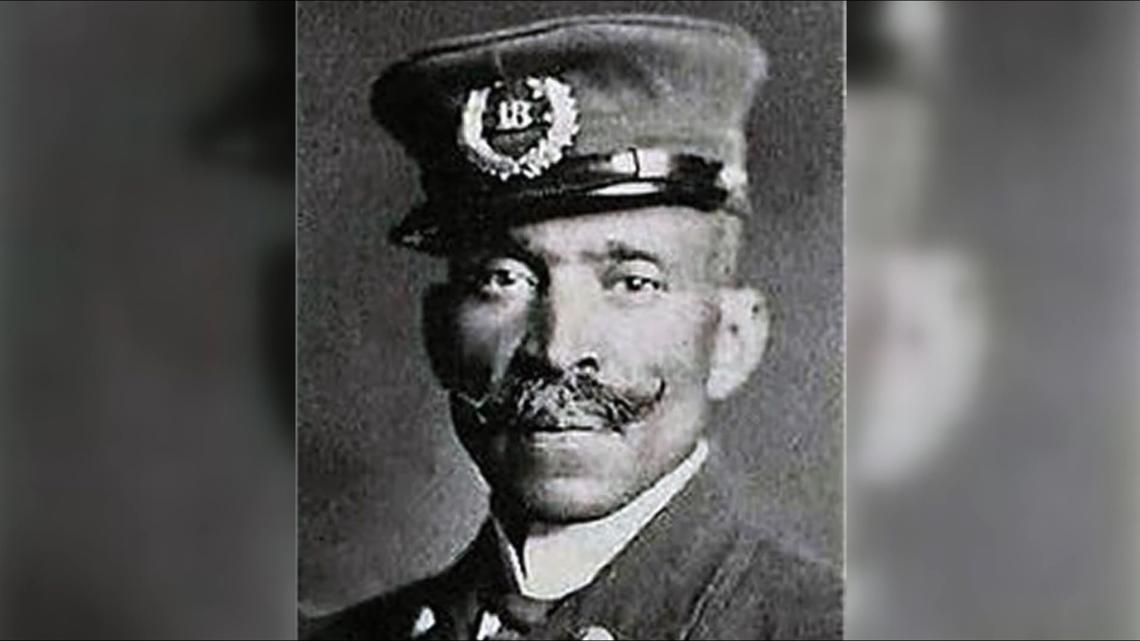

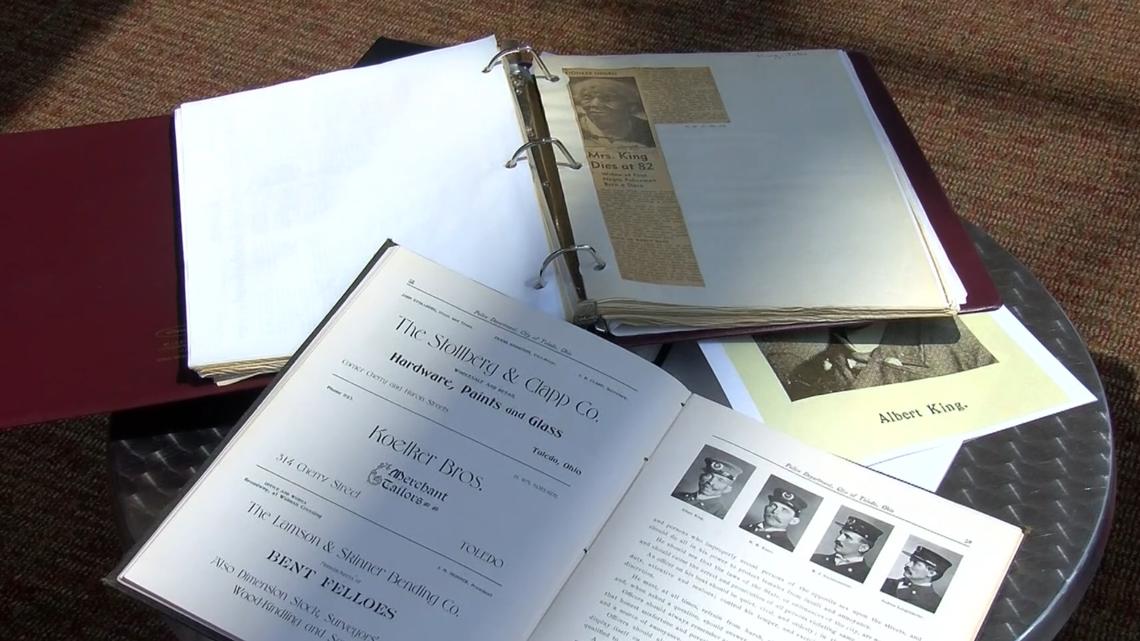

There, Julia became Toledo's first Black juvenile probate officer, and Albert was Toledo's first Black police officer.

"In the early 1800s, there were very few Black people in the state of Ohio. I think the 1800s number was around 337 in the entire state," said Janet Rhodes, a local historian for the Toledo Lucas County Public Library. "And that only went up to 1,900 around the year 1900. So very, very few people in the state, which meant there were very few people in Toledo."

Rhodes said Black Americans continued to face racism and other hardships throughout history, not just in the south, but also in Ohio and across northern states.

"A lot of people think that Ohio was a free state - a northern state - and that's sort of true," Rhodes said. "But, there were a lot of preventative measures in place to prevent Black people from living here. There were also things called Ohio's Black laws. Those were meant to prevent black people from moving to Ohio, which of course encompasses Toledo."

According to Rhodes, Ohio's Black Laws limited the Kings in their everyday lives, including their careers. Albert faced these prejudices on the police force.

"There was an interview his wife (Julia) gave in 1936 where she talked about him (Albert) and said that people were opposed to him being on the police force. It was actually the mayor that was encouraging of it. He wanted to make sure Black people had representation, which was very progressive at that time," Rhodes said.

Rhodes explained, "You had to carry documentation you were free. It wasn't necessarily a friendly time to be black in Ohio or in Toledo. So, the same holds true for Julia King for her to hold a position like that at that time; it was really remarkable."

The curator for the Forest Cemetery in North Toledo agreed.

"I think it's really important we bring their story to light to Toledoans so they can understand what the climate was like back then," said Robyn Hage, curator and historian.

Albert died in 1934, and the Kings' only child, Doris, died in 1921.

Following Julia's death in 1938, there was no one left to ensure her name would be added to the headstone.

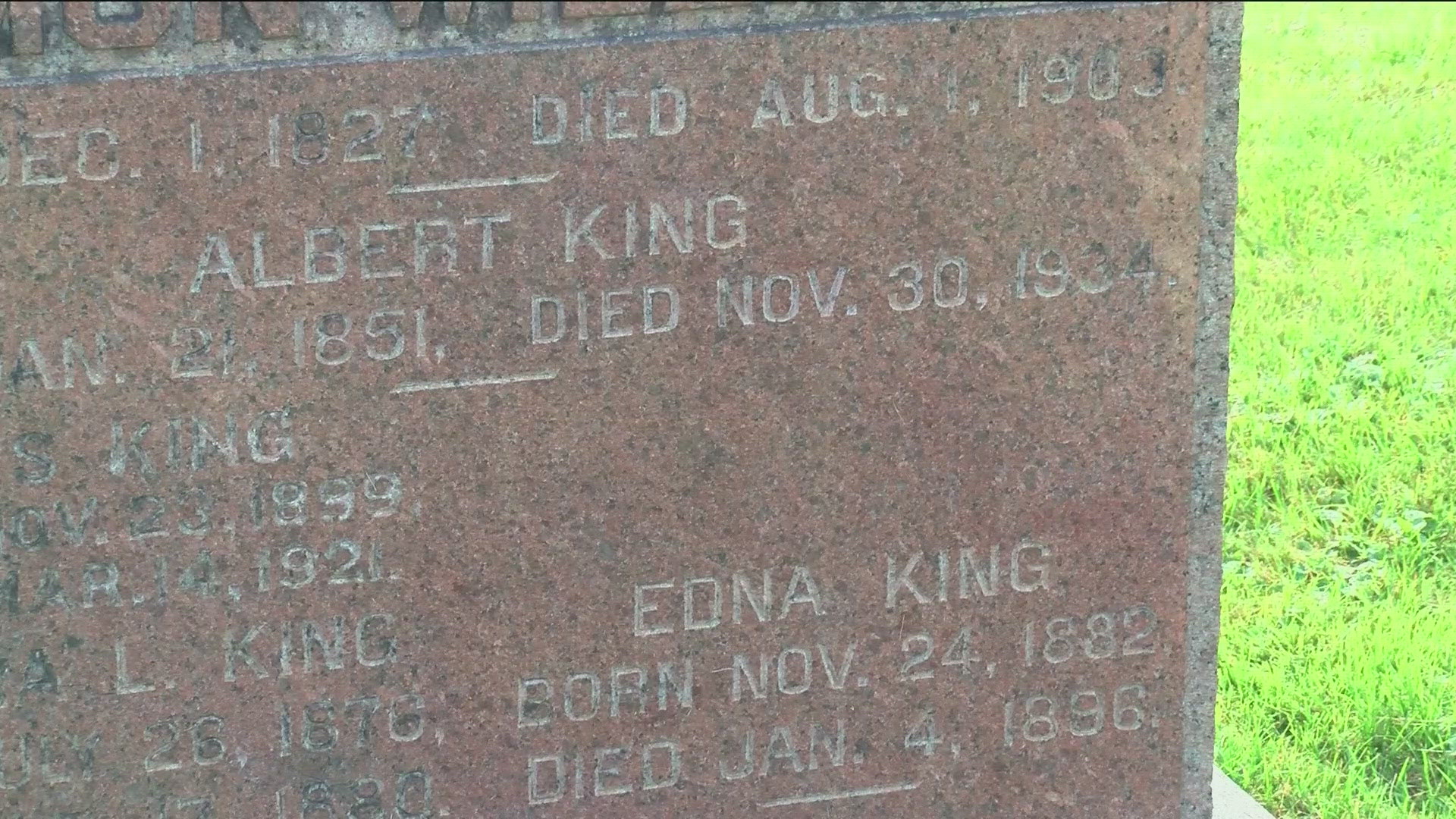

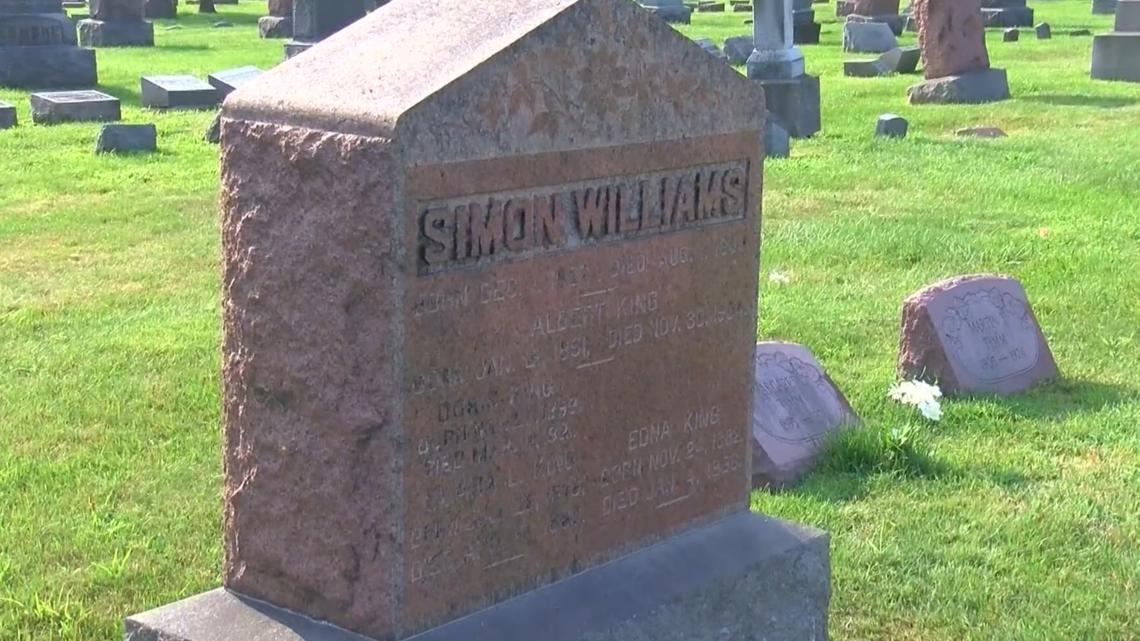

During a tour, Hage noticed the blank spot on Simon Williams' headstone, who was a boarder at the King household.

Hage said this intrigued her, which began her research into Williams and the King family.

After Williams' passing, a monument was created. Under his name, the King family was listed.

"So, if you look at this particular headstone, you'll see the name Albert King inscribed on it, but what you don't see is his wife, Julia Ward," Hage said. "Albert King was the first African American police officer here in the city, and unfortunately, after he passed away, there was no one left to get Julia's name inscribed on the monument."

Now, 86 years after Julia's death, Hage is ensuring Julia's name and place in history is not lost to time.

"So, what we're trying to do is raise the $625 dollars that's necessary to get her name inscribed on the monument, and we're trying to match the original font so that it looks complete. And we want to honor her legacy," Hage said.

Her reasoning?

"I think every life has value and everyone has a story to tell," Hage said. "It's very important to perpetuate Julia's memory by having her name inscribed on this monument, so she is not forgotten over time."

Though shocking to some, Rhodes explained it was common for Black individuals to not be listed on headstones.

"You know, I really think that speaks to just how spotty Black history is in general," said Rhodes. "There were a lot of barriers in place for Black people to record their history. We weren't allowed to read and write for a really long time. So we had oral history to pass things down, but that was person-to-person. Having these stories preserved was certainly not a priority of white people, but especially for Black people - they didn't have the tools for a very long time in order to do that."

In 1936, the Works Progress Administration Federal project "Born in Slavery: Slave Narratives, 1936 to 1938" recorded over 2,300 interviews with former enslaved people, including Julia.

"In the interview with Julia King, she talked a lot about a lot of other Black firsts in Toledo. So she talked about an orchestra conductor, the first Black student, and other things like that. How there wasn't a Black neighborhood during that time," said Rhodes.

Rhodes said though the King family represented some of the first African Americans in Toledo, they were also like any other Black family during that time, and that they deserve to be remembered.

"Remembering Black history is so essential, especially at a time when it is being removed from public institutions and not being taught," said Rhodes. "We have to understand what our history is in order to make progress."

Donations for Julia's name can be mailed or dropped off at the Woodlawn Cemetery located at 1704 Mulberry St., and they must include her name on the donation or check.

Editor's note: This story has been updated to correct the location for donations.

WATCH MORE FROM WTOL 11