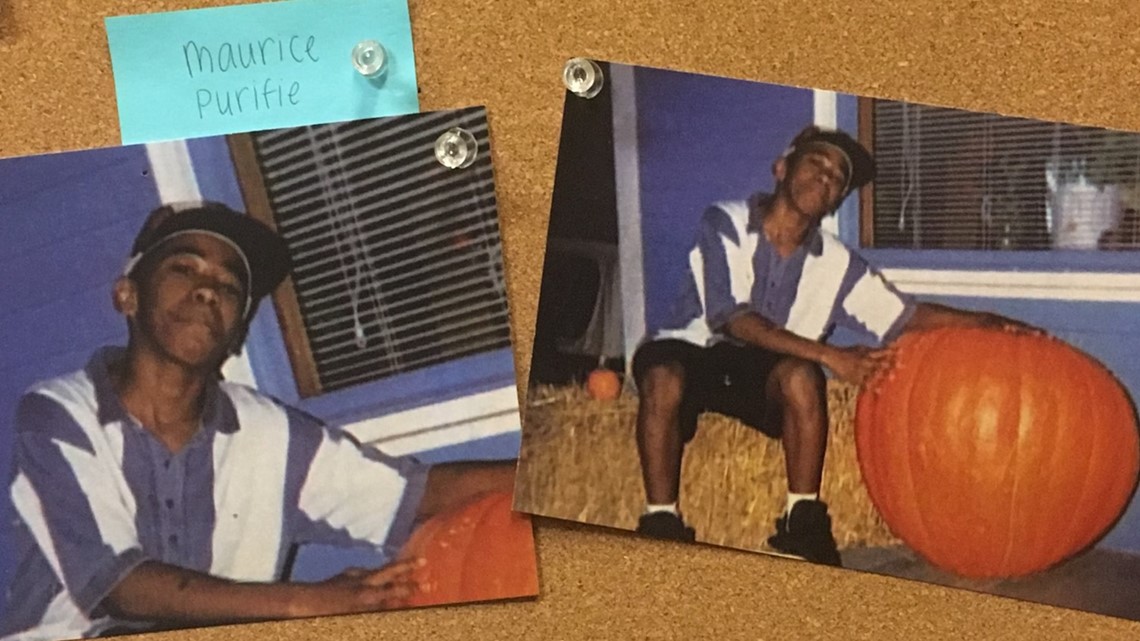

TOLEDO, Ohio — On May 23, I was sent a letter from the Ohio Innocence Project. The letter discussed the appeal of two men - Wayne Braddy and Karl Willis - who were convicted of murdering 13-year-old Maurice Purifie in central Toledo in 1998.

“The Ohio Innocence Project represents Karl and Wayne, who we firmly believe are innocent,” the letter read.

I’d be lying if I said my first reaction was, “Sounds good. Maybe they are innocent.” No, my first reaction was, “Yeah, right. Everyone in prison has a story about how the system has wronged them. There is a reason they were convicted.”

But that initial letter started me down the pathway of examining the sometimes terrifyingly fragile hands of justice. The journey has resulted in more than 600 miles of traveling. I have been to two prisons, a jail, the courthouse more times than I can count, and to the home of a convicted killer and rapist. I have had uncomfortable conversations with police and prosecutors. Rarely a week, or sometimes even a day, goes by without getting a phone call “from an inmate at a state prison.” I have tracked down - and surprised - a jury foreman and a trial witness, asking them to tell me their memories from a time period that they have tried to forget.

The journey has forced me to ask: “What if?” What if two men have been condemned to spending the rest of their lives in prison for a crime that they say they did not commit – and they really are innocent? Is it possible that something like that could happen to any of us?

It is an unsettling question that I asked Lucas County juvenile prosecutor Andy Lastra.

He tried to tamp down any concerns. “No one person can pull a name out of a hat and survive an investigation by this police department,” he said, in explaining that police will corroborate the testimony of any accuser and that your arch-rival can’t just accuse you of a horrible crime and get you sent off to prison.

But police - and prosecutors - have a hard job. Sometimes a crime has little physical evidence and circumstantial evidence has to be used.

Wayne Braddy and Karl Willis were convicted with no physical evidence against them. There was no DNA, no murder weapon, no video footage of the crime, no impartial eyewitness. They were convicted because of the testimony of a man convicted in the killing who is now out of prison because he cut a deal with the state to testify against Braddy and Willis.

It would be natural to assume that convicts are accomplished liars - and I’m sure many of them are - but Willie Knighten Jr. told me something interesting. Knighten spent years in prison for a murder he did not commit and has known Braddy and Willis for most of his life. He told me that there is this myth that everyone in prison believes he or she is innocent. Instead, he said, most of the people in prison are there on plea deals, and most killers will admit to their crime. But Willis and Braddy? He said they have never said they had anything to do with the death of Maurice Purifie.

The purpose of this story is not to assign blame - or guilt or innocence. The goal is to lay out the evidence I found in those thousands of pages of documents and to get you to ask: “What if?”

There were 144 exonerations in the United States in 2018. There are now 44 Conviction Integrity Units in the U.S. These units are dedicated to re-examining controversial convictions and getting fresh sets of eyes to look at them and ensure that they were just. Lucas County does not have a unit, though seven counties that are smaller do.

So the deeper questions I want viewers to ask are: “Do Braddy and Willis deserve to have their case looked at again by prosecutors? And “What can we do better in this area to protect the judicial process?”