The surgeries and ensuing pain and rehab have been a part of his life since 2003, the unfortunate byproduct of spinal stenosis.

But something was very different about the aftermath of his July, 2013, surgery, in which a surgeon implanted plates, screws and other hardware. By Labor Day, VanWinkle says, it felt as though he was getting stabbed – over and over.

The hardware had come apart. When surgeons opened him up, an extremely dangerous infection – Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, or MRSA – was discovered.

“The infectious disease doctor said it had been introduced during the surgery in July and was a slow-growing infection, similar to acne,” Diana VanWinkle, Mark’s wife of 30 years, tells 11 Investigates. “They don’t think it was from him. It was from the surgery.”

There is no way to say for sure what caused VanWinkle’s illness, but infections are not uncommon after spinal surgeries. A randomized trial of 314 patients released in 2016 by a team of doctors found that 12.7 percent of patients suffered an infection after a spinal fusion. That means more than 120,000 infections a year in the United States. For surgeries involving scoliosis patients, research has put the infection rate at between 25 and 40 percent.

“It was three months of antibiotics through an IV. Day in and day out, it was huge amounts of antibiotics,” Mark VanWinkle says. “I didn’t leave the house. I didn’t go outside. I didn’t leave the chair that I lived in for months.”

Eventually, his FMLA benefits ran out, and VanWinkle lost his job of 23 years.

“We could have easily lost everything,” Diana VanWinkle says.

It is pain and suffering that, in many cases, can be avoided, a local researcher believes.

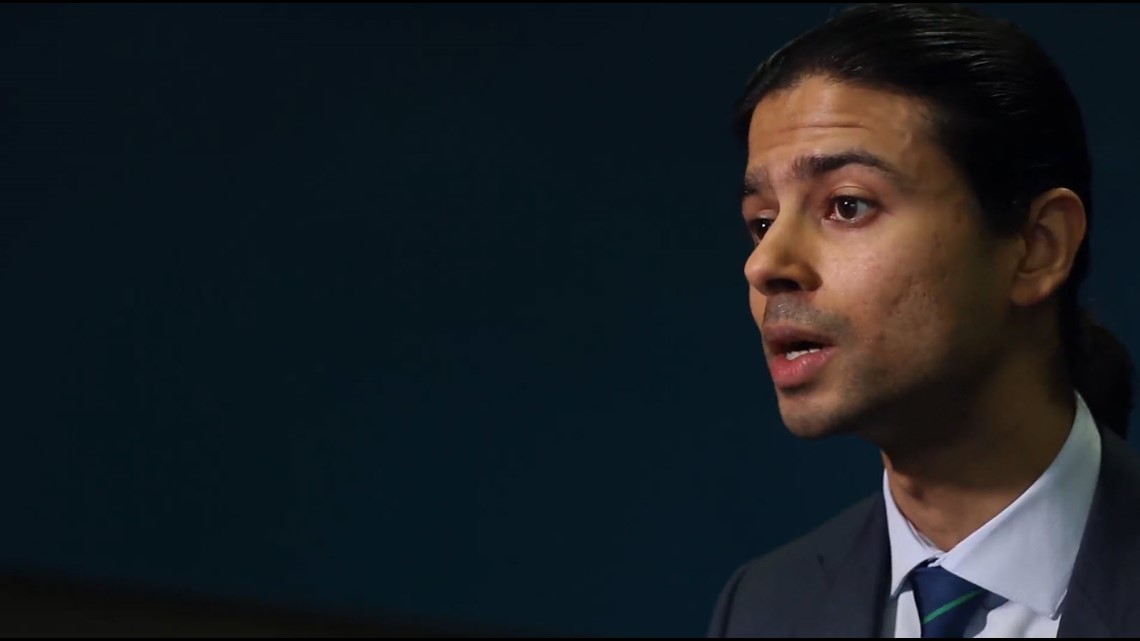

Aakash Agarwal, an adjunct professor of bioengineering at the University of Toledo and the director of research for Spinal Balance Inc., is driven by the goal of driving down infection rates. While not the main reason for his research, his grandmother died from an infection after a hip transplant. Agarwal’s belief is that almost all infections result from bacteria being introduced into the body during a procedure.

“There is evidence that most orthopedic devices used during a surgery are contaminated,” Agarwal tells 11 Investigates.

Regarding spinal surgeries, Agarwal’s focus has been on the pedicle screw. The screws are used for stability and support in spinal fusion surgeries. But Agarwal believes the screw can be a vehicle for infection, providing a pathway for dangerous bacteria.

But how does that bacteria appear on a screw in what is supposedly a sterile environment?

A surgeon has more than 100 screws of varying sizes available to him during a surgery.

“But about six are used in surgery. The rest are recycled. They are washed again with the dirty implements from the surgery,” Agarwal says.

Every screw that is not used during the surgery is required to go back into the hospital’s sterilizer – a dishwasher-like machine. It’s a procedure that some of the screws can go through up to 50 times before being put into the body. Several studies have agreed that, over time, the process can result in corrosion and bacteria on the screws.

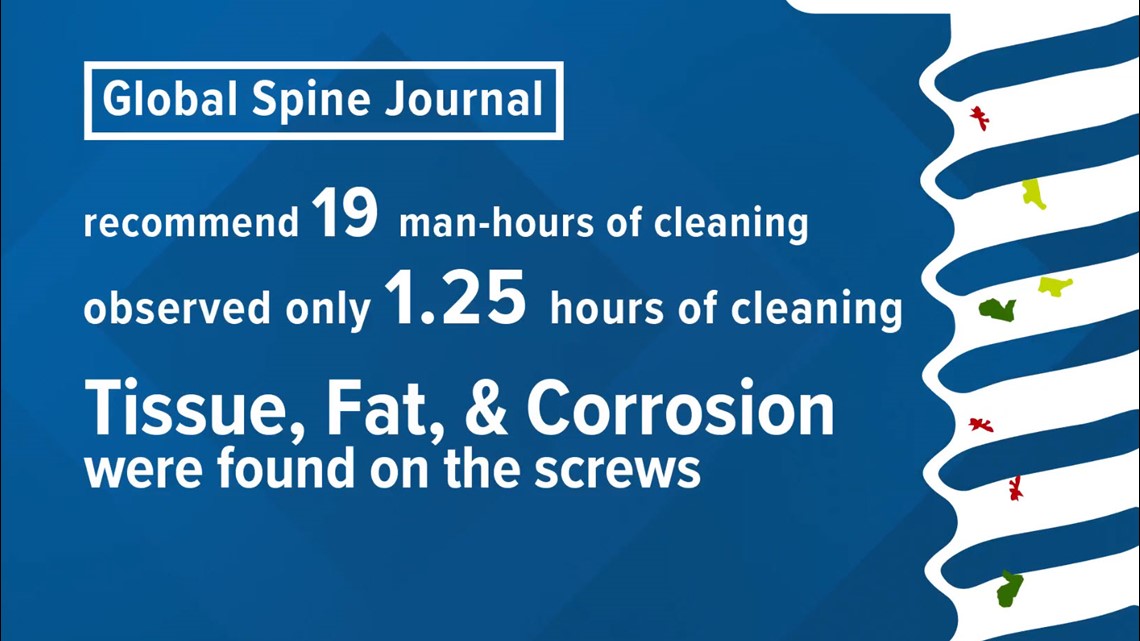

Agarwal led a multicenter study that was released in a number of journals last year, including Global Spine Journal. His study used an electron microscope to examine pedicle screws awaiting implant from surgical trays. The study was funded by the government’s National Science Foundation, of which Spinal Balance is a member.

“We randomly selected screws and opened it up and found things that we should not be finding,” he says

Tissue. Fat. Corrosion. Soap.

During repeated washings with bloody surgical tools, Agarwal believes material can get trapped in the many nooks and crannies of a pedicle screw.

His study noted that manufacturers recommended 19 man-hours to sterilize the screws. His team’s observation was that a little more than an hour was being used on the process.

While Agarwal’s research targets pedicle screws, the same procedure is followed for some orthopedic screws, particularly those used in trauma surgeries.

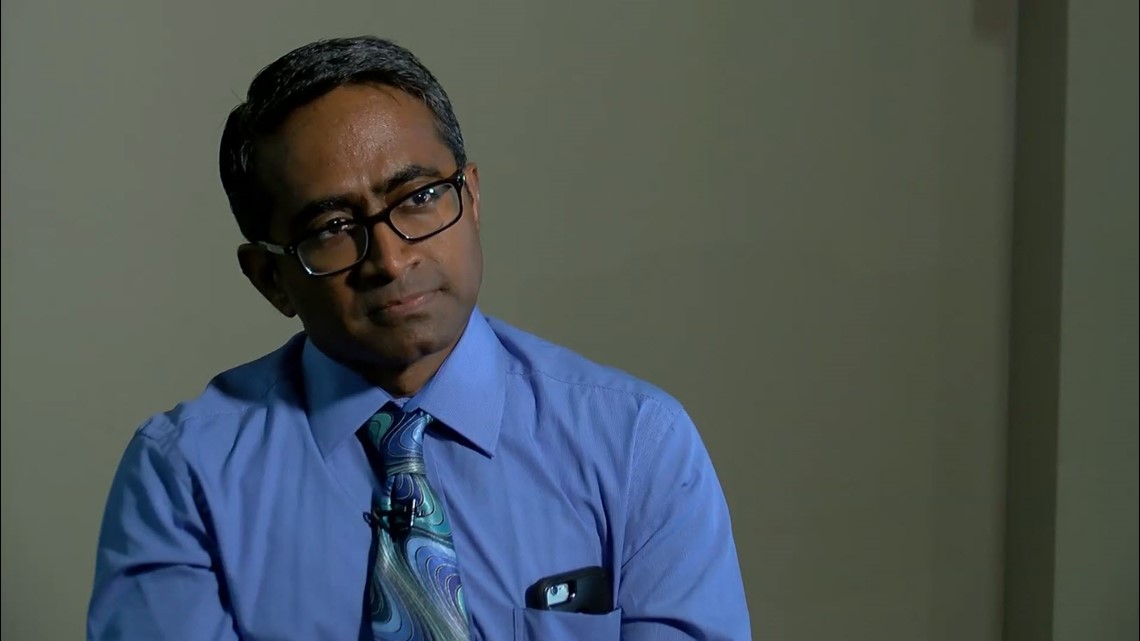

When asked whether it was possible that another person’s tissue, or even blood, was being implanted in some patients, Dr. Vithal Shendge, an orthopedic surgeon with multiple offices around the area, responded: “It’s highly likely because of the washing process. That’s a huge problem.”

Patrick Sherer of Findlay was recovering from a hip surgery when he tripped and fell, shattering his femur.

“They put a plate and 10 to 15 screws in my thigh, then I get an infection. It gets into the hip, and they have to remove that hip,” Sherer says.

Now, he is hooked up to antibiotics for more than five hours a day. He isn’t sure what caused the infection, but it scares the hell out of him to think that a sterile operating room might not really be sterile.

In 2008, Scotland mandated that all medical implants be prepackaged and not be repeatedly sterilized after Dr. Harry Burns, the country’s chief medical officer, noted that the sterilization process was flawed and was allowing for bacteria to be transferred into patients. Japan has moved in the same direction.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has not released any directives on the issue and indicated to 11 Investigates that it is important that hospitals follow recommendations of the manufacturer. They provided the following statement:

“It is important that sterile devices are sterile prior to implantation. However, FDA does not regulate the practice of medicine. State licensing authorities with oversight of hospital facilities, the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO), and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) have authority to review hospital procedures and practices. Healthcare facilities are responsible for following the device manufacturer’s validated instructions for use of pedicle screws and other medical devices, including either reprocessing instructions or instructions that devices are single-use only.”

Despite the agency’s statement, its mission statement says that the “FDA is responsible for advancing the public health by helping to speed innovations that make medical products more effective, safer…”

In Agarwal’s opinion, the agency is not addressing an obvious problem. He has petitioned the agency, asking them to ban reprocessing of medical implants.

Agarwal shared with 11 Investigates an email with the U.S. Department of Health's Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. In the email, he asked the agency who should address his concerns.

An official responded: "I have conferred with AHRQ program staff, who have informed me that FDA is indeed the federal agency with responsibility for addressing this issue."

But besides contamination during the sterilization process, there is another way in which implants are exposed to bacteria.

“These sterile implants are put in the patient in the sterile region, and it is called sterile, but it really is not sterile. There are people in there, people, patients, flora. They are being held, attached to the device, kept on the table and being exposed.”

In a video shown to 11 Investigates of a spinal surgery involving pedicle screws, it is clear that the screws are touched by surgical techs before they are loaded onto a device to implant into the body. While the techs are wearing gloves, those were the same gloves touching implements involved in the surgery.

According to Agarwal, studies have shown that simply changing gloves before “loading” the screw can reduce contamination by 60 to 70 percent. Using prepackaged screws, instead of trays of screws that have been resterilized, drives the contamination rate even lower.

That contamination can result in not only potentially deadly infections, but, according to a May study, also the failure of implanted hardware, similar to what happened to VanWinkle. The study, conducted by German doctors, was reported in the Journal of Neurosurgery: Spine. Researchers studied 82 cases in which hardware failed. In 54 patients, the pedicle screws had loosened because of previously unseen bacteria that caused a slippery layer of biofilm.

“People have to be aware that when you go in for surgery, the surgeon uses everything in his power to provide the best care for the patient. But the patient and the surgeon have to be aware that what they are being provided is not the best,” Agarwal says.

He says that the evidence is increasingly showing that the safest way to implant hardware is with prepackaged screws and with a guard that prevents the screw from being touched before being implanted. Spinal Balance makes those items, but Agarwal owns no part of the company and says that the products were developed as the result of studies showing the need.

Agarwal says, more than anything, that he wants to bring the awareness to the issue – for surgeons, manufacturers, and patients.

“Surgeons need to request that the manufacturers and hospitals provide implants in sterile packages and with a guard. Patients should request that their surgeon or their hospital find out options,” he says, before adding that the FDA needs to take action. “Why does the FDA exist? It exists to provide oversight for these medical devices and the best practices in using them. We can’t stick to what we knew 10 years ago. It needs to evolve to what we know now.”

For Dr. Shendge, the research should be a priority.

“Infection is the biggest disaster after any surgery. Maybe the rate is low, but when it happens in that patient, the rate is 100 percent,” Dr. Shendge says. “Once it happens, it is difficult to get rid of the infection without taking part of the bone that is infected. Once you have an infection, the chance of infection increases every time.”

The VanWinkles are frustrated that doctors have said very little about Mark’s infection. In fact, they say they were shut down whenever they tried to bring the subject up. But they are hopeful that the latest research leads to the implementation of Agarwal’s recommendations.

“If something so simple could prevent what we went through, I think it would be a great thing.”