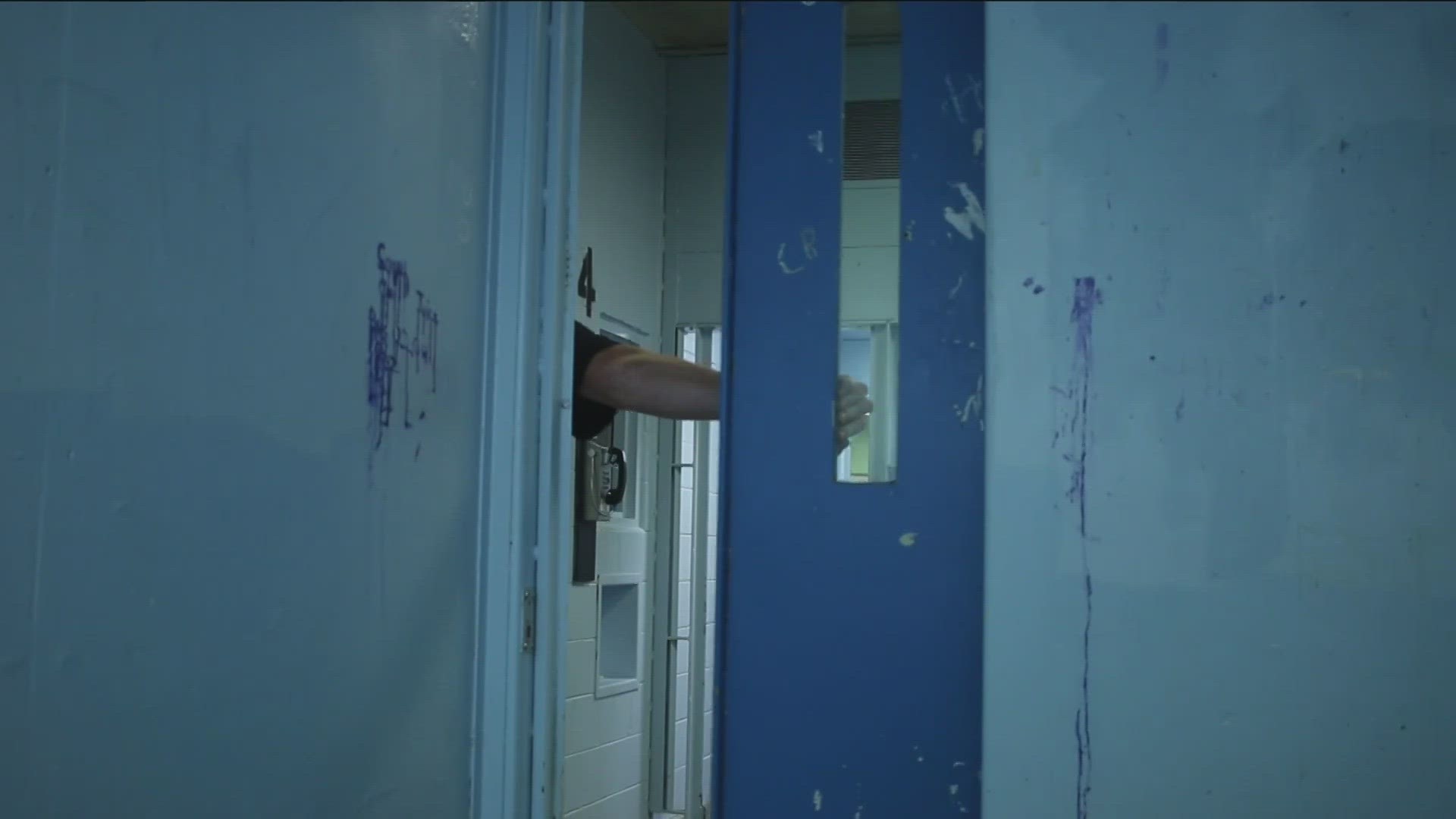

TOLEDO, Ohio — After professing their innocence to a 1998 murder for more than 23 years, Wayne Braddy and Karl Willis stood up in Judge Gary Cook’s courtroom on March 28 and accepted Alford pleas. Their aggravated murder charges were vacated and replaced with charges of involuntary manslaughter.

Willis addressed Judge Cook, saying, “I am an innocent man, but I am accepting this plea so I can go home.” Within an hour of the hearing, he was on his way.

The men gained their freedom, but they lost the legal ability to continue fighting for exoneration because they admitted that the state had enough evidence to convict them, even though they didn’t believe it.

Ohio Supreme Court Justice Michael Donnelly has a name for the deal offered Braddy and Willis – a "dark plea."

“It’s a plea offered to someone who has already been convicted," Donnelly said. "They are no longer under the presumption of innocence, and they are being offered freedom in exchange for clearing charges that have already been resolved. That’s the dark plea. It’s a level of coercion that I would describe as the legal equivalent of placing a gun to someone’s head and forcing them to confess to something that they don’t want to do.”

There have been four deals in Lucas County in the past year that would qualify as dark pleas under Justice Donnelly’s definition:

- Hector Alvarado, who was released in July after being convicted of a woman’s 2013 killing.

- Braddy and Willis, who were released in March. They were in prison for a 1998 killing.

- Stoney Thompson, released in November after being granted a new trial for three 2006 murders.

Lucas County Prosecutor Julia Bates has yet to respond to a request for comment about her philosophy on post-conviction deals.

According to data from University of Wisconsin law professor Keith Findley, 23% of inmates between 2010-2020 that had strong innocence motions determined by an innocence network were offered a plea deal.

“That’s an extraordinarily high rate because that means those are cases where they are agreeing to vacate the conviction or where the conviction has already been vacated based on new evidence of innocence," Findley said. "And yet they’re trying to cling to some version of a guilty judgment."

His research also found 41% of inmates rejected deals and continued trying to prove their innocence through the court. In those cases, he said every inmate ended up prevailing in court, meaning these were cases that prosecutors were on the verge of losing.

For Donnelly, he said it’s important to ask why prosecutors would even offer a deal to someone who already has been convicted.

“The conclusion I’ve come to is a prosecutor that had a good-faith belief in the integrity of the conviction would not offer a dark plea until he or she knew they were facing a new trial,” he said. “And the only reason they would offer it before they learn that is that they fear they are going to lose if it goes to a hearing.”

Findley said a prosecutor may believe in the conviction, but there are other reasons they give up the fight.

“It runs the gamut from them simply not wanting to be responsible for freeing someone in the off chance that something bad would happen later, to fear of civil liability for the county or the jurisdiction for a wrongful conviction, to downright maliciousness,” he said.

Some inmates across the country have gotten as much as $50,000 per year for wrongful incarceration. In the case of Braddy and Willis, a payout like that would amount to more than $1 million apiece.

As far as why an inmate would give up claims to innocence, the obvious answer is that they can earn their freedom much more quickly than if they continue to file motions.

Guilty without Proof aired in August of 2019. Based largely on findings by 11 Investigates, the Ohio Innocence Project was able to file a motion for a new trial.

Braddy and Willis were waiting on a ruling from the Sixth District Court of Appeals when the prosecutor’s office approached their lawyers about a deal – nearly four years after the airing of our investigation.

And victory is not guaranteed on appeal no matter how solid the innocence claim.

“You’re gambling your case, even though you may be innocent, on a system that’s already failed you once," Findley. "Remember all these people were already convicted in the first place. For those who are in fact innocent, their innocence didn’t matter. Why would they have faith the system would treat them better the second time?"

Thompson was offered a deal after spending 16 years in prison and after the appellate court ordered a new trial for him.

“We talked to him about it and he wanted to do it,” said his lawyer, Michael Stahl. “How do you know what’s the right answer? I don’t know what I would do in his shoes. It’s like you have a chance to go have a life again. And so he decided to do that.”

Donnelly said the simplest solution is the enactment of Criminal Rule 33.1, which in part would require a prompt hearing for those with claims of innocence. The Ohio Rules Commission is holding a hearing on the issue next week.

“A lot of people make arguments that this rule will open the floodgates,” Donnelly said. “There is this myth out there that everyone who is convicted in the criminal justice system maintains their innocence. That’s just not true.”

The recommendation came out of an Ohio Supreme Court task force chaired by Toledo appellate judge Gene Zmuda. Another recommendation was that the state establish an Ohio innocence commission to have independent parties examine claims of innocence.

When asked, all three men interviewed for this story said a countywide conviction integrity unit would be beneficial in Lucas County.

“Local prosecutors have an enormous amount of power. It’s almost unassailable,” Stahl said. “I like the idea of a conviction integrity unit. I would prefer to see it independent, and independent from trial attorneys involved in the case. I think it could be a great benefit, but it shouldn’t be something that makes it look like we’re doing something. It has to be something that actually does something.”

But Donnelly said that changes have to be made in Ohio’s post-conviction process.

“The stars really have to align for someone who claims that they are innocent,” he said. “You have to have a good lawyer, a judge willing to have a hearing not currently required under law. Sometimes you need celebrity involvement, and it shouldn’t have to be that hard. We should have a system where the primary goal is the truth.”

RELATED VIDEO