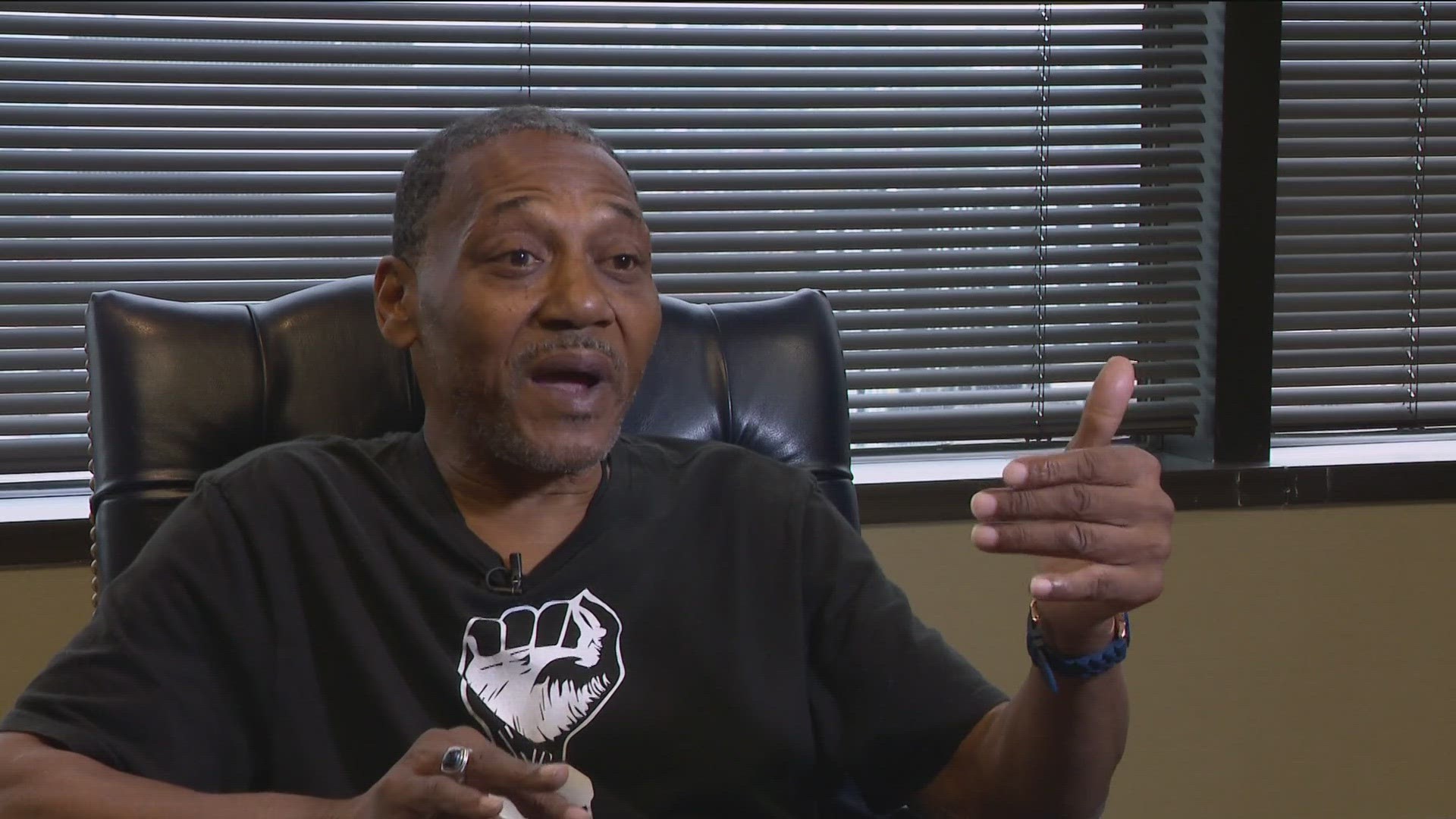

CINCINNATI — As he talks in a law office conference room, high above a downtown Cincinnati street, Danny Brown flicks his tongue around the inside of his empty mouth.

Years ago, he lost his teeth from a severe infection that almost killed him.

He never replaced them as an act of defiance against a system that kept him imprisoned for more than 19 years for a savage murder – a murder that the same system now says he didn’t commit.

“I want people to see that I’m not ashamed of who I am, but I want them to know that they made it difficult for me to get things I should have gotten,” Brown said.

Late last month, Lucas County Common Pleas Court Judge Lori L. Olender set Brown’s civil trial date for June 3.

If a jury decides he was wrongfully imprisoned, the Ohio Court of Claims will determine how much compensation he deserves for the two decades that were taken from him. Ohio currently awards a little more than $64,000 for each year of wrongful imprisonment, plus lost wages and attorney fees.

“We are extremely confident in Danny’s case,” Brown’s attorney, Bart Keyes, said. “We see what, I think, everybody except the state or prosecutor has seen.”

The death of Bobbie Russell

In December of 1981, 28-year-old Bobbie Russell was a mother of three, living in a Birmingham Terrace apartment, when she was murdered.

Police believe she was sodomized, raped with a broom handle and strangled with a wire from a Christmas tree in her apartment.

There was a witness to the crime – Bobbie’s 6-year-old son, Jeffery, who told police that Brown killed his mother. But Jeffery initially said Brown and another man were in the apartment. At trial, his story was that only Brown raped and killed his mother.

All these years later, Brown doesn’t deny that he knew Russell.

“We used to stay with my uncle. He was helping this lady move and he asked me to help move her,” Brown said. “We went over there, and that’s how I met Bobbie.”

Although Russell was about four years older than Brown, they briefly dated.

“She was cute. She was a little older than me, but I started talking to her and she was really nice,” Brown said. “She’s a beautiful person and had a beautiful spirit.”

He denies he had anything to do with her death, pointing to a small scar on his forehead.

“You see this scar right here? I got in a fight with this guy in my neighborhood. I was beating him and he picks up this adding machine and hits me square in the head,” Brown said.

He said the machine fell to the ground and his friends yelled for him to pick it up and use it. “I didn’t pick it up. I didn’t use it. I couldn’t find it in my heart to do that to someone.”

He shakes his head.

“I didn’t kill that girl.”

Two days after Russell’s murder, Brown was watching the news with a friend when a story came on about a murder at Birmingham Terrace. He jumped up when the victim was identified.

“I said, ‘I know her. That’s Bobbie.’ And then someone told me I needed to call home,” Brown said. “I call home and my mother said, ‘What did you do?’ I said, ‘What do you mean?’ She said the police were there, and I told her that I hadn’t done anything.”

But based on Jeffery’s identification, the police had zeroed in on Brown as their main suspect.

“I told my friend, ‘Hey, they think I killed this girl. You come on, take me down to the police station.’ I went straight to the police because I wasn’t going to wait another minute.”

Brown said he spent the night of the murder skating with friends and then hopping from house to house, just hanging out.

But he said he didn’t know where he was at exact moments throughout the weekend, just that he knew he was nowhere near the crime scene.

He believed the best thing to do was to cooperate with the police, and when they asked for specifics, he would guess.

“That’s the wrong thing to do with police because they can turn anything around, but I was in the company of 60 people the entire framework of when the murder happened," said Brown. "So there was no way possible I could have done the murder on the other side of town, then get back, look normal, have no blood on me. It’s an impossible scenario.”

Brown’s friends attempted to give him an alibi, but the jurors believed Jeffery’s testimony. On Sept. 24, 1982, Brown was convicted and later sentenced to life in prison.

“I always held on to the fact I didn’t do this, they can’t do this to me, but I was mistaken,” Brown said. “I kind of went into shock after the verdict. I had a mini breakdown.”

A second chance

In 2001, advances in DNA technology provided a new legal life for Brown. A semen sample at the scene matched the DNA of another man, Sherman Preston, who similarly killed another Toledo woman in 1983. He was also a suspect in several other murders. He never admitted to killing Russell and died in prison in 2018.

Brown was released in April of 2001 and his conviction was vacated, but he was only freed from the bars, not the suspicions.

“It’s still on my record that I was arrested for it. It shows I was accused of it, that this dude might be a killer,” Brown said.

Since being released he has been fighting to be legally exonerated, which would give him access to compensation, but also clear his record.

Lucas County Prosecutor Julia Bates has fought him on every appeal, insisting that Brown is still a suspect in the killing.

He spiraled. He developed bad habits, engaged in risky behavior, abused his body and let the anger consume him.

“I almost died three different times," said Brown.

At one point, he was in the welfare office when he suddenly felt sick and asked for an ambulance to be called. His blood pressure was out of control. He was in a hospital intensive-care unit. It took doctors more than a week to get his blood pressure under control.

“These are the consequences when you do this to people,” he said, shaking his head.

He still has family in Toledo but moved to Cincinnati several years ago. He expresses frustration that he trusted the system, believed that witnesses, a polygraph test he says he passed, being cleared by DNA would be enough for his name to be cleared.

He said the system is broken.

“The whole justice system is like when someone goes into a store to rob it. The person behind the counter says, ‘I’m gonna give you all the money. Take all the money. Just don’t shoot me.’ Then the person just takes his gun and shoots them in the head and heart," said Brown. "I feel like the system has done that to me.”

One more fight

In 1989, the University of Michigan began a national registry for exonerations. As of Tuesday, there have been 3,411 men and women freed.

Since Bates was elected prosecutor in 1996, she has exonerated no one, though there have been several claims of innocence.

In 2022, Stoney Thompson, Wayne Braddy, Karl Willis, and Eric Misch fought for new trials in Lucas County.

Like Brown, Willie Knighten is still fighting to be declared wrongfully imprisoned. Former Ohio Gov. Ted Strickland granted him clemency for a 1996 murder and he received a full pardon from Gov. Mike DeWine.

However, Bates also refuses to clear him of suspicion. Despite his battles, Knighten said he considers Brown the “grandfather” of claims of innocence in Lucas County.

“Danny Brown opened up the eyes and the doors for a lot of us. But at the same time, he came home with so much trauma, so much baggage, from all those years of being wrongly convicted,” Knighten said.

Brown could become the first Lucas County resident to be declared wrongfully imprisoned. Past efforts have failed because Bates has refused to rule him out as a suspect, which was one of the requirements under previous Ohio law. However, the General Assembly made a change in 2019.

“There was this hurdle that you had to prove no charges could or would be brought against the person with the wrongful conviction claim. With a crime like murder, there is no statute of limitations, so that charge could be brought at any time. All the prosecutor had to do to block compensation was say, ‘We still consider this case open or this person is still a suspect.’” Keyes said.

“In 2019, the General Assembly did something that, frankly, they should have done a long time ago. They made changes to the wrongful conviction law. One of the changes was to take away the ability of a prosecutor to prevent compensation by saying the case is open or the person is still a suspect.”

During the past several years, many states and cities have been taking a closer look at wrongful conviction claims, largely because of advances in DNA.

Last month, Lourdes University became the first school in the region to announce a program to review wrongful conviction claims.

In June, Lucas County Commissioner Peter Gerken told 11 Investigates that he is committed to starting a conviction integrity unit in the county. However, multiple emails have since been sent to his office asking for an update. No updates have been provided.

But Knighten and Brown believe that changes are coming.

“Lucas County is realizing that they’re not exempt. There are wrongful convictions that happen in other counties, why not here?” Knighten said.

“It’s a new age coming,” Brown said. “The prosecutors can’t keep doing it. The world is changing. Things are evolving,” Brown said.

Brown has earned two college degrees, including from the University of Toledo. He credits spirituality for turning his life around, but he also credits his mission.

“I need to be a spokesman not just for me, but other people in my situation, for other people going through this justice system,” Brown said. “This is my opportunity to attack that system.”

More on WTOL: