TOLEDO, Ohio — On Feb. 2, 1993, 16-year-old Eric Misch was brought to the Toledo Police Department’s Safety Building.

Police asked him about the August killing of Vernon Huggins in Wilson Park, a Toledo park that spreads out in the shadow of Woodward High School.

Huggins’ body was found near a building inside the park, his body badly beaten. The coroner said he died of blunt force injuries, which were inflicted by a combination of kicks, punches and a heavy object.

A tipster told police that Misch and his friends, members of The Bishops gang, were likely involved.

At some point during his interview, Misch agreed. He told Detectives Robert Leiter and James Anderson a story about how he distracted Huggins and Joseph Rickard, Louie Costilla, Mel Vazquez and Larry Vazquez then jumped the man. A robbery attempt spiraled into a murder, Misch told them.

The story was transcribed and used against him in a 1993 trial, which ended with him being convicted of murder and sent away to prison.

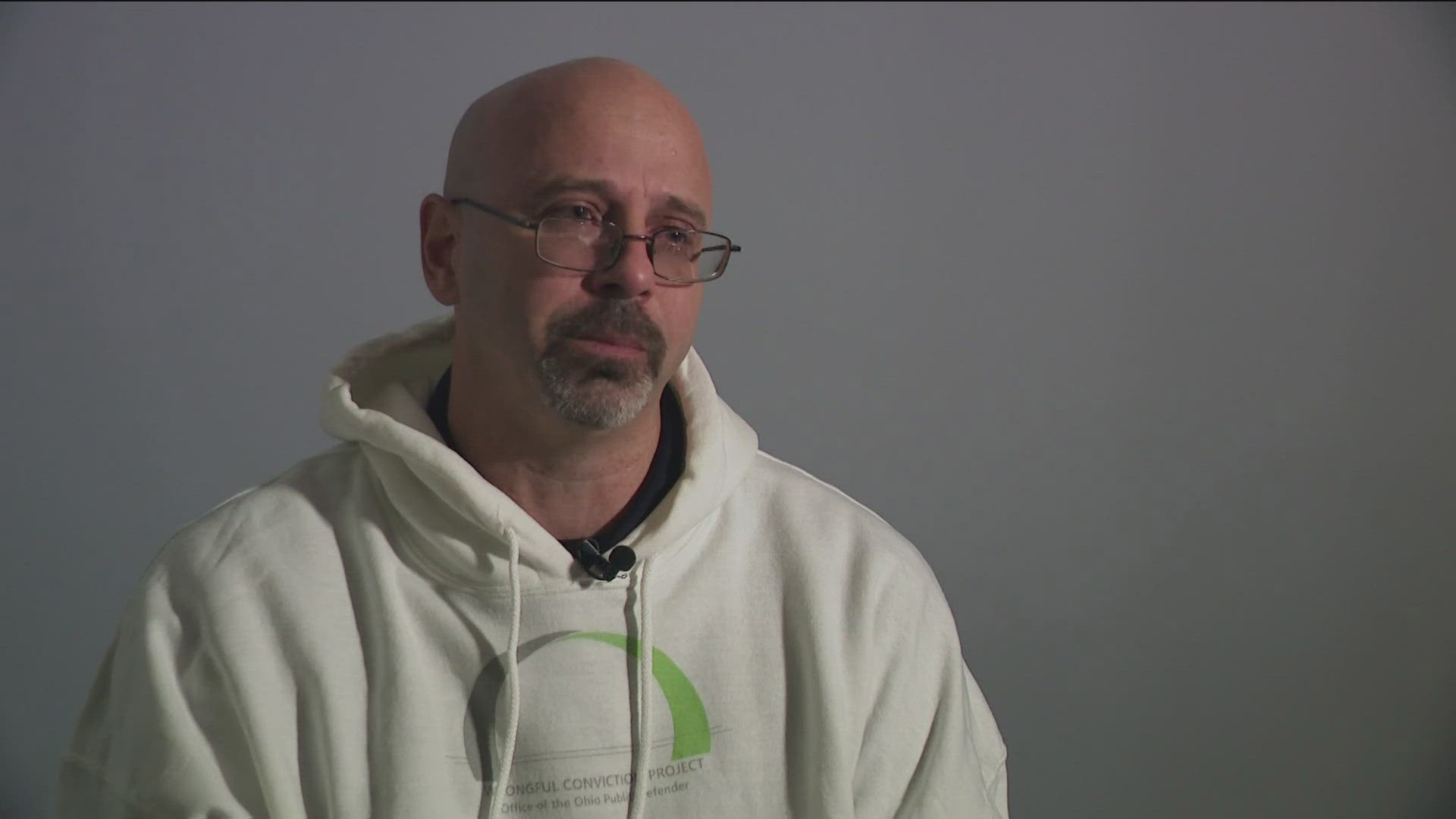

More than 30 years later, Misch said the story was nothing but lies.

“I was most definitely scared," Misch said. "They were coming at me, saying I was going to be locked up until I was 50 or for 50 years. I mean, who wants to go to prison for more than half their life?”

For the first time, Misch is telling his story. In previous times, police and prosecutors were in control of the narrative. But that changed in June when Lucas County Common Pleas Court Judge Gary Cook vacated his conviction and ordered a new trial. Last month, the prosecutor’s office ended a bruising legal fight that left the Toledo Police Department and the prosecutor’s office with a black eye. Charges were dismissed against Misch, but 26 years in prison cannot be easily forgotten or erased.

The University of Michigan’s exoneration database is littered with stories of false confessions. Those never in that position might wonder how someone could point the finger at themselves, but it happens often enough that it can’t even be described as unusual.

“I was scared. I mean, I didn’t know what else to do honestly. I just wanted to get it over with. I guess a lot of people just wouldn’t understand,” he said. “I came home and went upstairs. I was crying. I remember my baby brother coming in and asking what was wrong. I said I did something wrong and he goes, ‘Well, you’ve got to tell the truth.’”

When detectives called to let him know about the upcoming grand jury, he told them that it wasn’t true.

“I told them and then I got charged.”

On Dec. 9, 1993, the then-17-year-old Misch was convicted of aggravated murder and aggravated robbery.

“I believed that the truth was going to be told in court. Yeah, I believed they would see the truth and I would come home," he said.

But the jury didn’t.

“Honestly, everything went numb. I guess it was like you can’t hear nothing and you are standing there in shock,” Misch said of the reading of the decision. “I didn’t know how to react. I went up to the floor (of the jail). I started crying in my cell.”

As one legal chapter closed, another would eventually open. After years of telling anyone who would listen that he had nothing to do with the murder, Misch convinced the Wrongful Conviction Project to take his case in 2011.

“Everything that Eric said in his application checked out one by one," Joanna Sanchez, the director of the Wrongful Conviction Project said. "We started looking at the things he was saying and they’re all checking out. The first thing that we noticed was there was no physical evidence implicating him."

The courtroom fight turned into a public records fight.

“We submitted public records requests to the Lucas County Prosecutor’s Office and the Toledo Police Department because we wanted to get as much information we could about the case,” Sanchez said. “We kept not getting records for the first months of the investigation. We’d get some records from them later on, but not those first few months. I think we did close to 10 public records requests over the years.”

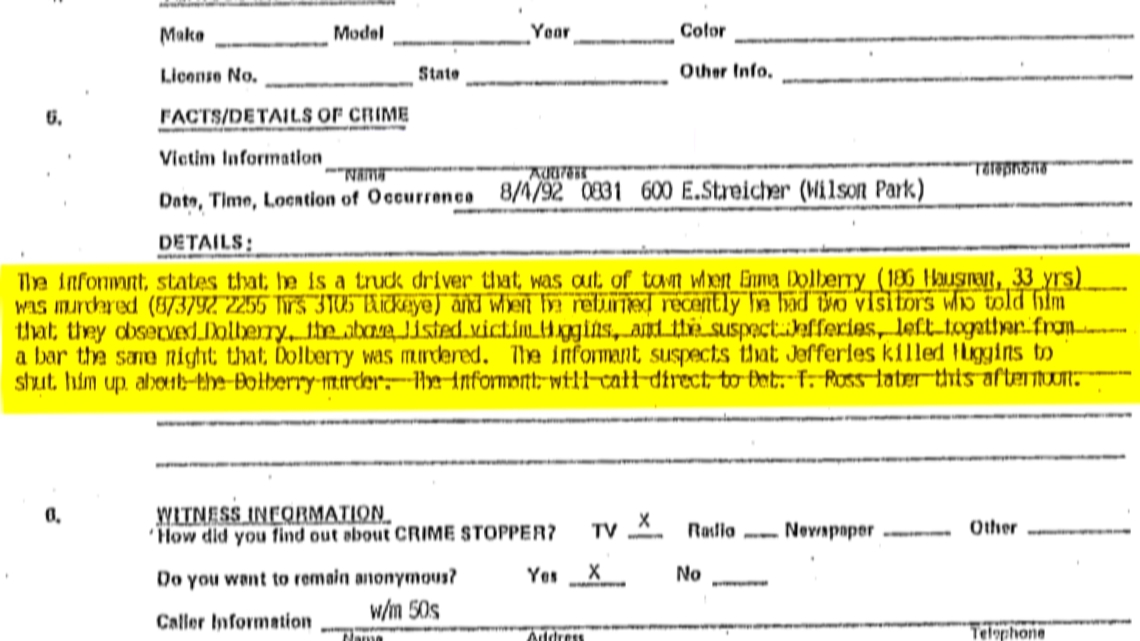

The persistence paid off beginning in 2018 when records began to flow in. At first, there were transcripts of police interviews, including with Misch, but then there were Crime Stopper tips. Some of them were shocking in their apparent importance. Important, but they had never been mentioned before. The prosecutor’s office had not even seen them.

“There was one document that was just shocking and impactful," Sanchez said. "I messaged my co-counsel and asked, ‘Am I reading this right? Are you guys seeing what I’m seeing?’ Everyone responded, ‘Yeah, this is monumental.’”

The monumental document was an interview with Huggins’ uncle, who told police that his nephew was confronted by his girlfriend’s family members about a burglary at her home. They believed he was involved. One of the men was carrying a table leg, similar in size and weight to what a witness at Misch’s trial said was used to kill Huggins. After being confronted, Huggins hid inside the home and did not leave until he was asked to leave much later in the night. He was alive hours after prosecutors said Misch and his friends killed him.

But there were other tips, including from a caller who said Huggins was in a bar that night with Lee Jefferies, who would kill a woman hours later. The caller said Huggins was killed to prevent him from talking.

Jay Gast, a prosecutor’s investigator, later uncovered more potential evidence, including DNA found on a bottle beside Huggins’ body. The bottle was sent to a state crime lab to be tested. DNA on the bottle hit on a Huggins acquaintance, a man who initially told the Wrongful Conviction Project that he didn’t know Huggins. It was a lie.

“I think anyone who looks at this evidence knows how important it is, and the state, the prosecution, they have an obligation to give evidence like that over to the defense. That did not happen here,” Sanchez said. “I wasn’t there. I can’t say why that evidence didn’t make it to the prosecutor’s office or why that evidence didn’t make it to the defense team. It should have, but it didn’t.”

It was likely clear to anyone examining the case that there were Brady violations, one of the most common reasons cases are overturned. The case law is rooted in the Supreme Court’s 1963 Brady v. Maryland decision in which the court ruled suppressing evidence that would be favorable to the defense violates due process. Even though the prosecutor’s office never saw the evidence before trial, it was known by police and not disclosed.

Even with the likely violation in their pocket, it still took Misch’s attorneys more than five years to get a court to clear Misch, demonstrating the difficulty of overturning wrongful convictions.

“Wrongful conviction cases are so hard. They are an uphill battle. You fight, you fight, you lose, you appeal, and it just takes so much to win,” Sanchez said. “But any judge that looks at this is going to see what we are seeing.”

As the case crawled through the judicial system, Misch survived in prison, working in maintenance, in the kitchen and studying to eventually earn an associate’s degree from Findlay University.

“I went through anger during the first part of my years in prison…anger and frustration about being there. But if that’s what you focus on, it’s not going to be helpful and you’re just going to be miserable the whole time,” Misch said. “You want to hang around positive people, even though you are in a negative situation. I hung around a lot of positive people.”

He was paroled in 2020, a free man, but a man with the convicted killer attached to him.

“It was rough. I had people tell me they were going to hire me, do my background check and see a felony. They’d ask if it was older than seven or 10 years. Of course, it’s older than that, so they’d say they weren’t worried about it. But then they’d find out what it was for and they’d tell me they couldn’t hire me.”

But the personal toll was difficult too as he tried to build a relationship with his daughter, who was born right after he went into prison. There has not been a relationship. When he was asked about it, the tears flowed and he put his head in his hands and rocked back and forth for nearly a minute.

“I was not able to be her father,” he said. “And that was a main goal of mine…to be a father.”

He had little to say about compensation, but his case seems to be a clear example of a person being compensated for wrongful imprisonment. The amount of compensation varies from year to year, but the most recent amount set by the auditor’s office is $64,186.92 per year of imprisonment. Misch would need to file suit to be declared wrongfully imprisoned, then he would need to go to the Ohio Court of Claims for a judgment to be determined.

He is the first person to be exonerated of murder in Lucas County. He would also be the first to be compensated if he chooses to pursue that path.

For now, he’s settling in as a husband to his wife, Trinah, who he married in 2022, and as a step-father to her children. He’s also learning about technology.

“There was a lot of stuff to learn. Cell phones weren’t around when I went to prison, Facebook, none of that stuff. My little brother literally has to show me how to use my phone,” he said, chuckling.

One day, he hopes to return to prison – as a free man – and bring the inmates a message.

“Keep the faith in themselves if they’re truly innocent. Keep your faith, have faith in God. I mean, I struggled with it, but I’m starting to see that he really has laid out a path for me."