The battle over cattle: 11 Investigates hidden costs of Williams County large-scale farms

Environmentalists and an Amish farming community battle over cattle, manure and the protection of Lake Erie.

Calves huddle together in fields that stretch out on both sides of county roads 1 and K in Edon.

In another field, a large herd of tagged cattle wanders over to see why a group of people are gathered near their fence.

Barns for the animals dot the Williams County landscape. In some areas, partially built barns are coming together. In spots, the barns are near each other, separated only by a gravel driveway.

Near one of those locations, an argument erupts on the roadway as an agitated woman screams at a man who is leaning on the window frame of his large white pickup.

“How do they comply with permitting? They don’t get permits. I filed 10 complaints against them myself. … I’m tired of looking at cow manure,” the woman screams at the man.

After several attempts to counter the woman’s complaints, the man apparently tires of the conversation.

“I’m holding up prosperity by sitting here. You folks have a good day,” he says as he drives away with a wave.

For two years, sides have formed in this Williams County battle. On one side is the Williams County Alliance, a group known locally as “the lake people.” On the other is a group led by Schmucker Farms, a large Amish family that controls 50 square miles in the far northwest corner of the state. On that land, they raise close to 100,000 calves and cattle that will eventually be shipped to JBS Foods, the largest meat producer in the world.

The battle is being waged atop the Michindoh Aquifer, in the St. Joseph River Watershed. Those creeks, streams and rivers eventually wend their way to the Maumee River and into Lake Erie.

Some of those waterways are dangerously polluted. If you ask the lake people why, the answer to them is clear: There are thousands and thousands of cattle living within too small of an area. And that many cattle leave behind a lot of manure.

Chapter 1 The Watershed

The Michindoh Aquifer supplies water to portions of Michigan, Indiana and Ohio. It is the sole source of drinking water in Williams County, which is home to rivers and creeks that comprise the St. Joseph River Watershed. The St. Joseph River begins in Williams County, travels across the Indiana border, where it converges with the St. Marys River in Fort Wayne to form the Maumee River.

A series of creeks and streams feeds into the St. Joseph River, including Fish, Bear and Tamarack creeks. 11 Investigates has obtained months of water analysis for those creeks performed by Jones & Henry Laboratories in Northwood.

E. coli and nitrates

Each of the creeks has various levels of pollutants in recent testing. A reading of 1,000/MPN (most probable number) for E. coli would shutter most public beaches to swimmers. A June 6 reading of Bear Creek registered more than 24,000. Tamarack Creek was at 4,600. Fish Creek was 1,300. Bear and Tamarack and Bear creeks also had extremely high nitrate levels. High E. coli readings are the result of human or animal waste. High nitrate levels are often from waste products.

Those creeks are surrounded by various Schmucker cattle farms.

Sandy Bihn, the executive director of the Lake Erie Waterkeeper Association, has been alarmed by the dramatic rise in the number of cattle now being housed in Williams County and has worked with the Williams County Alliance to push for state intervention.

“What changed in our watershed that caused this to happen?” Bihn says. “It’s concentrating animals, too much manure.”

Chapter 2 Schmucker Farms

For more than 40 years, the Schmucker family has raised cattle in northwest Ohio, northeast Indiana and southwest Michigan. But in late 2022, they partnered with property management firm Wagler & Associates in an attempt to obtain a Special Exception Use to open a facility to raise 8,000 calves.

The effort was unanimously rejected by the Board of Zoning Appeals.

“I was involved with a group in Indiana to fight the 8,000-head facility,” says Susan Scatterall of the Williams County Alliance. “It was 5-0. … After that is when it really exploded. I mean it outrageously exploded with the buying of the properties and bringing in the animals.”

The Ohio Revised Code said any farm that holds 1,000 or more animals is considered a Concentrated Animal Feeding Facility - or a CAFO - and is required to obtain a permit, which subjects the facility to additional testing and monitoring.

Splitting parcels, adding cattle

After the Board of Zoning Appeals decision on Jan. 23, 2023, there were a large number of properties in Williams County that applied to be split by members of Schmucker group.

When a parcel is split, rather than being limited to 999 animals before a permit is required, a barn can be put on each half of the split parcel, allowing 1,998 animals.

11 Investigates requested parcel-splitting records from the Williams County Auditor’s Office. Since the beginning of 2023, 23 different properties with connections to Schmucker Farms have been split.

When Scatterall reached out to the Ohio Department of Agriculture about the transactions and series of barns being built, she received the following email from Samuel Mullins, the ODA’s chief of livestock environmental permitting: “The method of parceling off land and constructing two identical operations without common ownership is a legal loophole to avoid permitting. So at this point, there aren’t any laws that have been broken. They are technically not required to obtain a permit to install because they are legally not considered a concentrated animal feeding facility. In other words, we do not have the authority over the construction of these facilities.”

In a later email, Mullins writes: “We have to find a way to close this loophole. It is a problem.”

11 Investigates had a 15-minute phone conversation with Michael Schmucker, a representative of Schmucker Family Farms.

He was asked if there was a plan to buy property and split parcels to avoid permitting requirements. He did not directly answer the question: “Our No. 1 goal is we want to be good stewards to the land and put this manure back out onto the ground to where we don’t need to use a lot of chemical fertilizers.”

The Department of Agriculture has little power over a farm with fewer than 1,000 animals, but it does have power over a farm’s handling of manure and its threat to waterways.

In the spring, enforcement agents received a complaint and swept across a series of Schmucker farms.

Chapter 3 ODA enforcement

Besides the calves huddled beside county roads 1 and K in Edon, there is something else that’s obvious – piles of manure. Some of it lies atop the ground, other can be seen filling barns.

In April, responding to a complaint, ODA agents inspected a series of Schmucker-related properties. Eleven cases resulted in notice of deficiencies, with items needing to be addressed by either August, September or December. Additional properties were hit with warning letters. But all of the cases involved improper manure management. Some involved intentionally housing more than 1,000 animals without obtaining a permit.

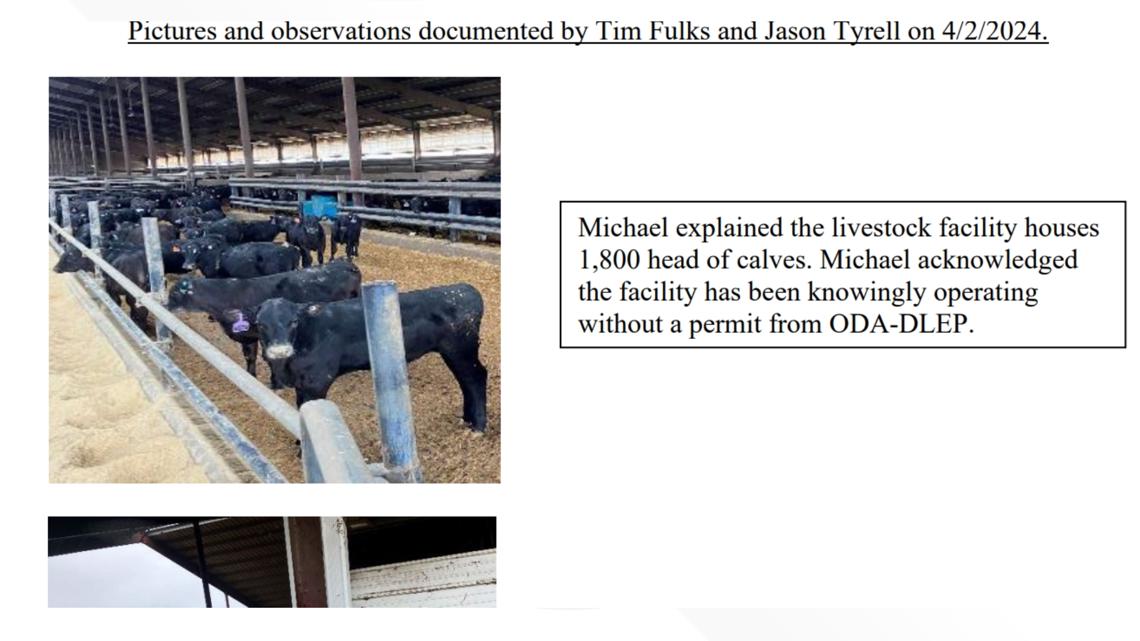

11 Investigates has obtained hundreds of investigative documents. Michael Schmucker served as guide for a review of the Schmucker properties, according to records.

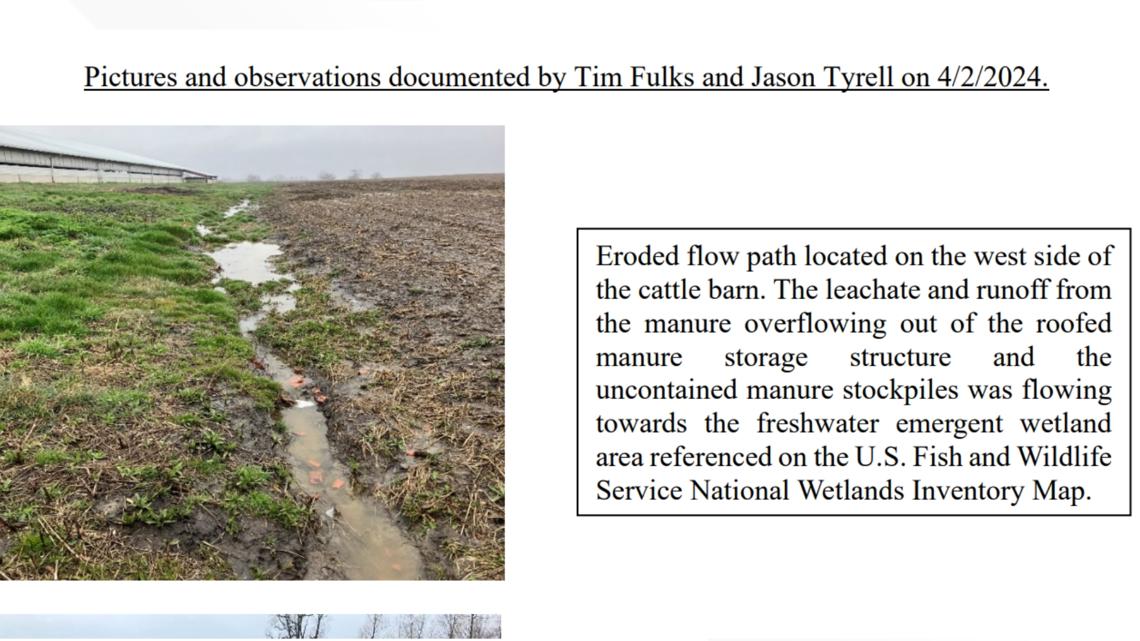

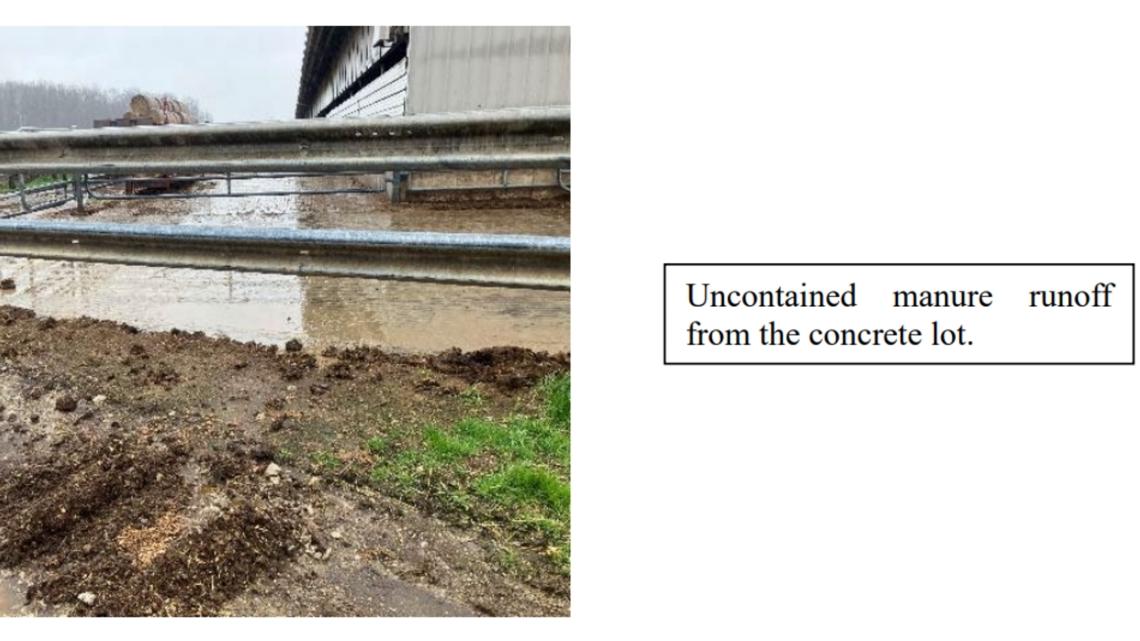

On April 2, agents inspected Matthew Schmucker’s property on County Road K. Findings were similar to other inspections at other Schmucker properties.

1 farm, 1,800 cows

The inspection discovered large amounts of manure outside and also under structures with a roof. In many areas, the manure was not contained and was running toward creeks or other wetlands. In addition, it was discovered that Matthew was housing 1,800 head of cattle, knowingly violating permitting rules.

He was given until Sept. 1 to take corrective action to contain the manure runoff and also to begin an application for a permit to house that many cattle.

An inspection of properties owned by Noah Schmucker Jr. discovered that he had been housing more than 1,000 cattle since Jan. 3, 2022, again, knowingly violating permitting rules.

“Those two properties were properties were properties we had just purchased. Our goal now is that we’re going to be talking to ODA about their two barns and try to get permits,” Michael Schmucker says.

Manure storage plans

He says the goal of the property owners is to build manure storage facilities that will keep all the manure contained and under a roof. He says many ODA recommendations – and orders – have been completed, though some will not be completed by Sept. 1.

“I think it’s a reasonable deadline, but we do feel blessed to be working with people from the ODA who understand that we can’t make all these things happen overnight. There are a few things that we are working on, but we’re not going to be done by Sept. 1.

When asked about the investigations, Ohio Department of Agriculture Director Brian Baldridge provided the following statement:

“The Ohio Department of Agriculture currently has open enforcement actions into multiple properties in Williams County. ODA’s divisions of Soil and Water Conservation and Livestock Environmental Permitting have recently inspected the properties in response to multiple complaints and are in contact with the property owners to ensure compliance with Ohio laws regarding permitted livestock facilities and manure management. Because there are open enforcement actions and ongoing investigations, we cannot provide any additional comment at this time.

“ODA takes very seriously its role in regulating farms and livestock operations. No farm or livestock facility of any size is permitted to pollute the waters of Ohio. ODA ensures the facilities are following state laws and regulations, specifically Ohio Revised Code Chapter 903 and Ohio Administrative Code Chapter 901:10, which are designed to protect both surface water and groundwater quality, provide authority to ODA to conduct routine inspections and complaint responses, and authorize the state to take enforcement actions against entities in violation.”

Chapter 4 The 'lake people'

They know that some Williams County residents derisively refer to them as “The Lake People,” but members of the Williams County Alliance wear the term as a badge of honor.

Sherry Fleming, Scatterall, Lyle Brigle, Tim Bricker, along with help from Bihn, have waged a battle against the Schmucker properties for more than two years, not because they dislike the farming family or their right to own cattle or farm, but because they believe they are operating with little oversight.

Noah Schmucker has been a prominent name in the cattle business for close to 50 years. His seven sons and four daughters have expanded the business. A third generation is likely to expand it more.

“What Noah Schmucker is doing hasn’t happened before,” Fleming says. “I don’t think it’s happened on this scale.”

She is referring to the splitting of parcels to jam as many cattle into the region as is possible.

“It’s a loophole. It needs to be fixed, and that’s where our state legislators are not stepping up to the plate, because they’ve been made aware of this,” Fleming says. “I place as much, or even more, blame on the legislature for not doing anything. The regulatory agencies can only act on the authority they’ve been given.”

Brigle has compiled folders of documentation on Schmucker farms. He put together an extensive PowerPoint presentation for state officials into the history and background of the explosive growth in cattle in the region.

“Northwest Ohio can’t support this amount of cattle,” Brigle says. “Northwest Ohio is one of the most highly tiled areas because it used to be the Black Swamp, and we’re lacing tile 40 feet apart, so anything you spread on it, especially liquid manure, gets into the tile system quicker. Once it’s in the tile, it goes to the streams, to the St. Joe’s River, to the Maumee, and to Lake Erie.”

Tiling is a plumbing system, of sorts, under agricultural land to whisk away excess sub-surface water. Its presence would allow easier access to main waterways. Bricker has been overseeing water testing for the group.

“The most dramatic numbers we are seeing are the elevated E. coli levels,” Bricker says. “But we are also testing for ammonia, nitrates and phosphorous.”

A water agreement between the United States and Canada aims to lower the phosphorous levels in Lake Erie by 40 percent. While agricultural farmers have been able to dramatically reduce their phosphorous contributions to the lake, the overall levels have not fallen, meaning other sources are contributing. Williams County Alliance members put part of the blame squarely on Schmucker Family Farms and legislators.

“(The Schmuckers) are gaming the system,” Brigle says. “They know how to manipulate it and our legislature is doing nothing to protect what should be protected and what they’re elected to protect.”

It’s an ongoing battle with the alliance that Michael Schmucker says he doesn’t want.

“I hope to be able to go into my little town of Edon or my hometown of Hamilton, Indiana, and we hope we can get along with everyone,” Schmucker says. “I want to help the public, teach them and show them what we’re doing. We’re trying to do things the right way and we’re trying to be Christian people. I want my walk to show that I am a Christian.”