TOLEDO, Ohio —

As the war against racism continues, dialogues on race relations are beginning to become more front and center across the country, world, and even right here in our own community.

The death of George Floyd, a black man who died at the hands of a white officer in Minneapolis, has sparked the outrage and protests from a collective diverse group of people around the world for several weeks now - but the frustration has been felt by Blacks for years.

The goal to simply be heard is slowly being answered through voices of change.

Monday

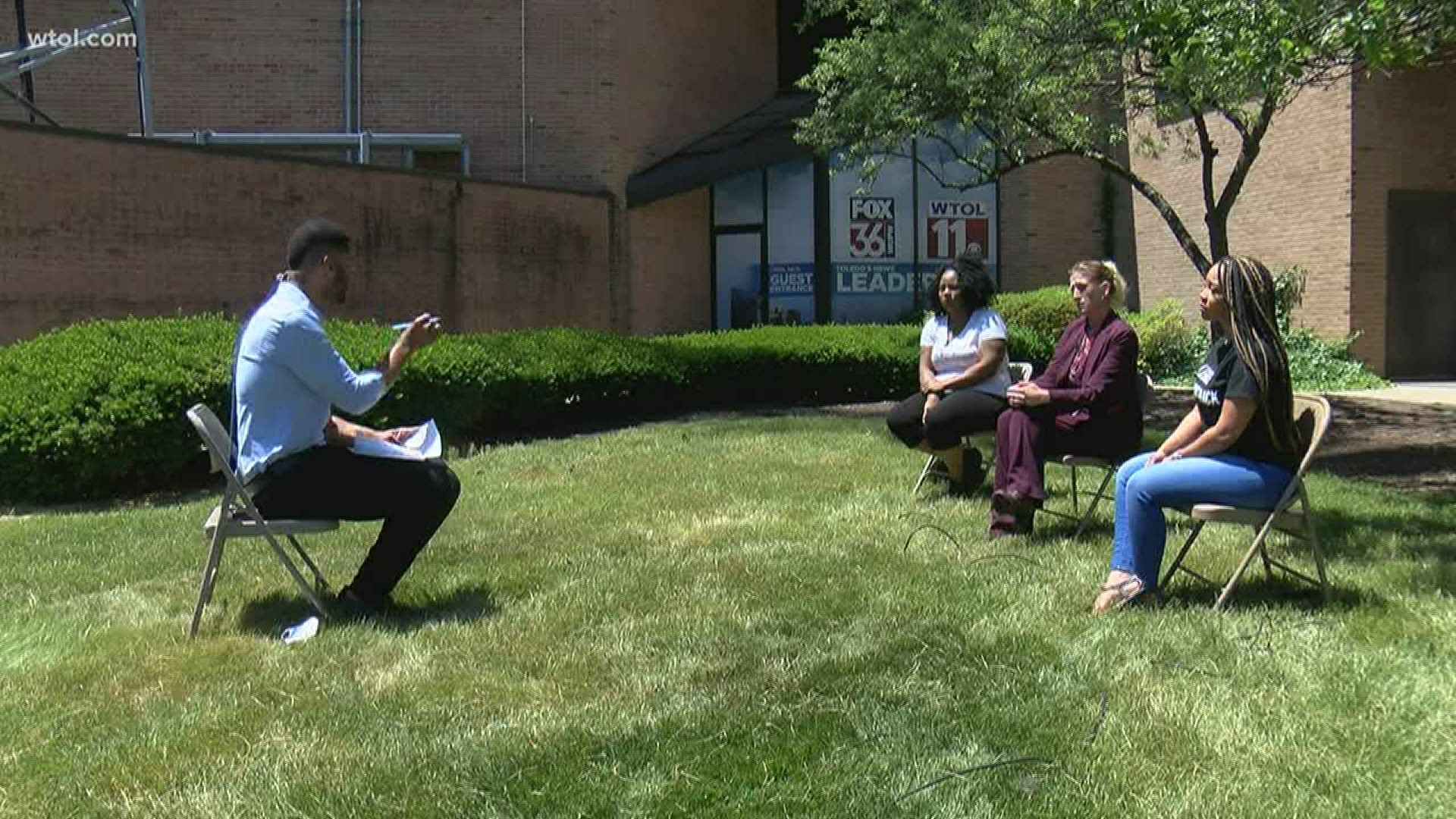

WTOL 11’s Andrew Kinsey spoke with Litisha Easter-Scott and Tiara Armstrong, two black mothers raising black sons, and Sarah Driftmyer, a criminal defense attorney and a white mother of a white son.

After watching George Floyd spend his last moments of his life crying out for his mom, Litisha, Tiara and Sarah discuss how that affected them as mothers and their experiences navigating issues of embedded, systemic racism while raising and protecting their children.

WATCH HERE

The conversation

Q: What emotions did you feel watching that video, hearing a grown man calling out for his mother?

A: Tiara – Me personally, I couldn’t finish it. Um it’s tough watching a grown man, a grown black man at that, you know, crying out for his mom. In the last minutes of his life. As a mother you’re a nurturer, you’re supposed to be there protect, to guide, to love, to care for, and to not be there you know, that’s heartbreaking. I couldn’t watch the whole thing, I watched snippets and bits and pieces. But it’s tough so...

Litisha – I'm the same as Tiara, I've only seen snippets of it. I haven’t been able to bring myself to watch it just because I know how I feel as a mother, even when my kids are outside playing in another room playing and you hear that cry ‘mom’ and my heart just immediately drops to my stomach because I don’t know if one of them has a broken bone or you know if they’re just horse-playing. So for something as serious as he was going through in the last moments of his life, for him to just call out for his mother and then she’s not living and he’s calling out for his mother, it breaks my heart to even just think to even see the little pieces of the video that I've seen and I will not bring myself to watch it because I know it will break me. It’ll make it hard for me to sleep.

Sarah - I personally just imagine what it would be like if it were my son and I was watching that after the fact and just seeing and feeling so helpless and knowing that his last thought was about you and there’s nothing you can do and the people that are supposed to help, are the ones that actually did it.

Q: Tiara and Tish, as mothers of young black boys, what are some of your daily fears, your daily struggles?

A: Tish – For me I memorize what my kids have on, before they leave home, if they’re going to school or daycare or out with their dad, who I am married to a black man. I memorize all of their clothes just because if you hear something on the radio or as big as social media is, you know people post stuff and they go 'there goes a situation on this street, these people have on these kind of clothes' and I do a mental dial back in my head like ‘What did my husband have on, what does my kids have on’ and you know I just couldn’t fathom you know something like that happening to me. I shouldn’t be, or we as black women and mothers and sisters and wives, shouldn’t be as worrisome as we are when it comes to the black men and boys in our lives, but unfortunately, we’re at that point.

Tiara - I agree with Tish. Memorizing what they wear, I need phone numbers of everybody you’re with, what location are you going to, even if it’s quick change of route ‘hey I'm going to the store, I'm going to be here in 10 minutes,’ so I know in 10 minutes, if you didn’t call me, I need to call you. Even for my son, when he’s out with his uncles or aunts or cousins, I need to know who all you are with so I can have an accountability for everybody. As mothers, we can’t be there every step of the way and at some point we have to allow our children to go out in this world and make their own decisions and choices and live freely but it’s hard to live free when you still feel like you’re in bondage, when you still feel like you have to take hold of the things your kids are allowed to do, the people they’re allowed to be around you know? And self checking, making sure I go over the rules with my son before he leaves the house. It’s not just you can just go outside and play or you can't just go freely to your sporting events. Let's go through our daily routine. Let me pour into you so you’re confident when you walk out that door, that no matter what you’re able to face you need to know what you need to do, it’s tough.

Q: Sarah as a white mother, do you empathize with these moms and are the concerns the same for you?

A: Well I absolutely empathize with them and its just kind of surreal to sit here and listen to what they have to go through every day. Probably the most relatable situation is when my son went to the protests, and after Saturday I was worried for his safety and that’s just one day one protest. And these guys worry every day just going to school or the store. I mean that’s something that I don’t do. And it’s horrible and they shouldn’t have to.

Q: As an attorney, you are in the courthouse every day. Justice - it's suppose to blind, impartial, objective for all. Is that the case when it comes to black men?

A: Oh absolutely not. I see kids, high school kids or recent graduates, smart kids that have had no contacts with the criminal justice system, get pulled over for something like tinted windows or they were in an area where Shotspotter went off. And these are good kids who are treated like absolute criminals. And without them knowing exactly how the police expect them to react, if they question authority at all, they get turned on and I don’t know, they're put into positions I would never want to happen to my son and I mean I see it all the time. I seem them treated poorly all the time.

Q: Is this a fear for you all, that one day your sons could be targeted or even profiled, simply because of the color of their skin?

A: Tish - Absolutely. At what point does my son, at what point does my son become a threat? I have a 2-year-old and 7-year-old, my husband is in his 30s. At what point in between that gap does my become a threat to you because of the color of his skin? Why can't he walk into a store and so some shopping or why can't he walk down the street or his car, his nice car with tinted windows without you think he may have a gun, when you're the one with a gun on your waist? Why is my son a threat? At what point? When he's 12 years old, when he's 26 years old? You know what I mean? When he's out in the workforce as a grown man? At what point does my 2-year-old, 7-year-old, at what point does he become a threat and why is he a threat?

Tiara - I agree. Black children in general are in a stage of adultification. When they’re babies, it's ‘aw they're cute, your son is cute, what’s his name, how old is he, how many months is he?’ The minute he loses the innocence, he’s targeted. My son is 9 and he looks like he’s 12 so, at this point, and my husband can attest to this, we have to have those conversations because he’s at that age. And it's sad to say we actually have an “age” where you can be targeted, although his heart is pure and he’s innocent, what they see on the outside is not innocent. You know he could be with a group and his best friend is white, but they’re not treated the same outside of the classroom. Heck not even in the classroom, but at 9 they don’t see that for each other, but as adults we can see you know. Just yesterday we were riding in the car and my son is the most lovable person in the world, he hugs and loves on everyone that’s just his character, there’s a group of white ladies standing outside on the corner and just out of the window we’re just laughing and giggling and he waves and says hi and I just watched to see what the response would be and some waved back, and the others gave a glare and it was kind of like “eh we’re going to push it off,” or “why is he looking at, or saying something to me?” And the fact that I had to pull my car over and explain to my son what you can and cannot do when you approach white women, is sickening. It’s sickening. And he doesn’t understand that. For me to say son “you have to say hi in a certain manner” or “you can’t say when there’s too many people” and he’s innocent. And the question he kept asking was “but mom why? I just want to say hi.” And you cant do that. And he watches and mimics his father. So his father is a barber, he works in the barbershop. Everyone knows the rule, you say hello when you greet the person, if you’re out and about, even if I can't shake your hand I nod my head to acknowledge your presence, but at what point cant you do that? And that’s when we experienced yesterday. At 9? Why can’t he just say hello and it be OK and there’s no backlash? And I know he felt what I saw, because he would have never questioned, “why I can’t do it that way” and before I even opened up my mouth it was “mom why didn’t they speak back?” It sucks. It sucks.

Q: How important is it to have mom allies, who understand your situation like Sarah?

Tiara - It’s very important. We grow up with the saying “it takes a village to raise a child.” I heard that my entire life. I never understood it until I became a mother and the fears you have as a mother raising a son or daughter, as Black or African-American is tough. So to be able to call, if it’s Tish or your own mother, hey I just need a little bit of advice, how do I go about this situation can you pray for me? Cause right now I'm having fears and anxiety. I don’t know how to deal with them or put them out there without it coming across, or without my son seeing the fear that I have. I think it's very important that we stick together because there may be a time I’m not there, but maybe you know my son. Let me introduce you, so if I’m not there you have this person to call on, and I think we do a very good job making sure, especially our generation now, we’re bringing that back that it takes a village to raise a child, so if I see your child out and about and I’m able to, whether I'm the parent or not I'm the advocate. And that’s what we have to be nowadays. An advocate, an ally. So if we can branch the gap between white and black, even if it's a white mom. 'Hey did you see my son?” Step in. Because now you have a voice, you are there, use your voice.

Q: Sarah do you think this is a conversation we’ll be having some 20 years from now.

A: Sarah - I hope not I hope things would be different then, but I guess my son is 24 years old and I don’t think much has changed from when he was a child, unfortunately. As much as I did think things changed before, with the recent events and with what I see every day in the criminal justice system I just don’t think anything has changed. So hopefully, everybody can make a difference now, so we don’t have to go through this in 20 years.

Q: Tish, what's the answer? How do we bridge the divide moving forward?

A: Tish - My opinion I just feel like, anyone, whites, I was asked approached recently at work you know with everything going on, what is something that she could do to help the situation you know without going down to protesting and everything and my response was “to use your voice. Use your platform on social media to influence the people who are around you. Get them to see that we are all not threats. Get them to approach us in a different manner, to approach us in a different light. Influence the people you surround yourself with. Get them to see things through our eyes, get them to see things the way you see it, and that in turn will help us and it will help the situation. Because at this point, there is nothing that white people can do physically because at this point it’ll just make all of the situations worse. Use your voice, be an advocate for us, and in the end will that in turn will help us Black people altogether.