President Trump ordered his health secretary to declare the opioid crisis a public health emergency Thursday — but stopped short of declaring a more sweeping state of national emergency.

In an address from the White House, Trump tried to rally the nation to pay attention to a growing epidemic that claimed 64,000 American lives last year, and advocated for a sustained national effort to end to the addiction crisis.

"No part of our society – not young or old, rich or poor, urban or rural – has been spared this horrible plague," Trump said.

First Lady Melania Trump, speaking at the White House before the president, said “drug addiction can take your friends, neighbors and families. No state has been spared.”

To respond to that crisis, Trump signed a presidential memorandum ordering Acting Secretary of Health and Human Services Eric Hargan to waive regulations and give states more flexibility in how they use federal funds, said four senior officials responsible for crafting the administration's new opioid policy. The officials previewed the action to USA TODAY on condition of anonymity because they were not authorized to speak ahead of the president's announcement.

Trump first promised to declare a national emergency to combat the crisis on Aug. 10, and repeated that pledge last week. Speaking to reporters on the south lawn of the White House Wednesday, Trump touted a "big meeting" on opioids, and said a national emergency "gives us power to do things that you can't do right now."

But there's a legal distinction between a public health emergency, which the secretary of Health can declare under the Public Health Services Act, and a presidential emergency under the Stafford Act or the National Emergencies Act.

The latter is what the president's own opioid commission recommended in July. Declaring a state of national emergency would give the president even more power to waive privacy laws and Medicaid regulations.

James Hodge, a law professor at Arizona State University, said a "dual declaration" — of emergencies by both the president and the Health secretary — would give the administration more tools to fight the epidemic, but that any emergency would be a welcome response to the crisis.

Trump's decision to go with a more measured response, a public health emergency, demonstrates the complexity of an opioid crisis that continues to grow through an ever-evolving cycle of addiction, from prescription pain pills to illegal heroin to the lethal fentanyl.

But the legal powers Trump is invoking were designed for a short-term emergencies like disasters and infectious diseases.

By law, a public health emergency can only last for 90 days, but can be renewed any number of times. There are 13 localized public health emergencies already in effect for Hurricanes Harvey, Irma, Maria and Nate, and the California wildfires.

The opioid action would be the first public health emergency with a nationwide scope since a year-long emergency to prepare for the H1N1 influenza virus in 2009 and 2010.

Thursday's designation gives the administration specific powers to marshal federal, state and private resources. Those emergency powers would:

► Allow patients to get medically-assisted treatment for opioid addiction through telemedicine. Current law generally requires in-person visits for doctors to prescribe controlled substances. But for people in rural areas like Appalachia — where the opioid crisis has taken a particularly heavy toll — qualified doctors can often be hours away.

► Give federal and state governments more flexibility in hiring substance abuse specialists temporarily and shift federal grant programs for people with HIV/AIDS to get substance abuse treatment.

"I think our general feeling is, that's a good step, but it’s a temporary step, and it’s a transitional step," said Jim Blumenstock, chief of health security for the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials.

► Make Dislocated Worker Grants available to people with opioid addiction through the Department of Labor. Those grants are usually available to people put out of work by a natural disaster, but a public health emergency could also make those grants available to people in treatment. Labor Secretary Alexander Acosta told the opioid commission last week that pain and addiction sideline millions of American workers: Of men aged 25-54 not in workforce, 44% had taken a painkiller in the last day, according to the Council of Economic Advisers.

► Tap the Public Health Emergency Fund, a special fund that gives HHS maximum flexibility in a health crisis.

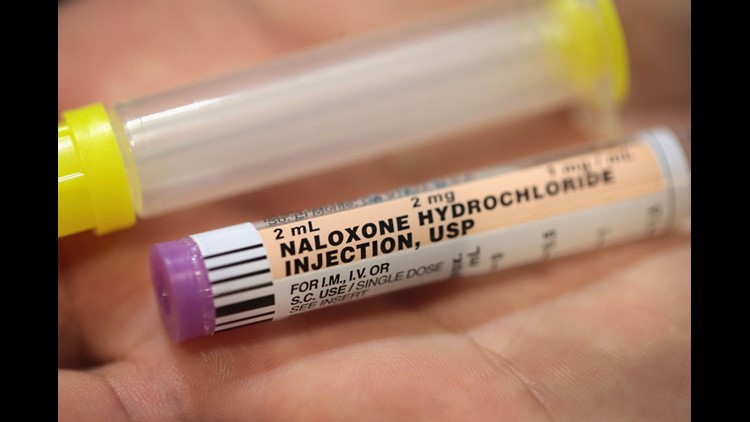

However, that fund has just $57,000 in it, said Bill Hall, a deputy assistant secretary of Health. The city of Middletown, Ohio could spend almost twice that this year on naloxone alone. Naloxone is a drug that can instantly reverse the effects of an opioid overdose.

Administration officials said the broader national emergency declaration was unnecessary because the government can clear some hurdles through lower-level action.

The Department of Health and Human Services expects to issue guidance soon emphasizing that health care providers can communicate with the families of overdose victims situations without running afoul of health privacy laws. HHS has also approved waivers to some regulations in four states, giving them the flexibility that a national emergency could have provided.

New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie, who chairs the president's opioid commission, told USA TODAY that a public health emergency should put pressure on Congress to act.

"My view is that this action sends a clear signal from the president that he wants money appropriated into that fund," he said. "And it gives Congress a place to go with that money to give the administration some flexibility to use it to be able to use it to deal with some of the most pressing parts of it."

Christie's top priority: Getting naloxone into the hands of every first responder in the country. "That will bend the curve back in terms of lost lives," he said.

One administration official said there was no specific funding request that would accompany the emergency, and House and Senate appropriations committees said they hadn't had any discussions with the administration on it.