WASHINGTON — A jury convicted two members of the Oath Keepers of seditious conspiracy on Tuesday, finding militia founder Stewart Rhodes and one of his top lieutenants plotted to forcibly oppose the government following the 2020 election.

Jurors deliberated for three days before finding Rhodes and Kelly Meggs, the militia's Florida state leader, guilty of the rarely used charge. The jury acquitted the remaining defendants — Kenneth Harrelson, a U.S. Army veteran also from Florida; Jessica Watkins, an Army veteran from Ohio; and Thomas Caldwell, a retired U.S. Navy intelligence officer from Virginia — of seditious conspiracy, but found each guilty, along with Rhodes and Meggs, of multiple other charges, including convicting all five on a felony count of obstruction of an official proceeding.

Rhodes, a former U.S. Army paratrooper and Yale-educated lawyer who founded the Oath Keepers in 2009 during the early days of the Obama administration, was convicted of seditious conspiracy, obstruction of an official proceeding and tampering with documents. Jurors acquitted him of conspiring to obstruct an official proceeding and to impede members of Congress.

Meggs, who led a group of a dozen Oath Keepers into the U.S. Capitol Building on Jan. 6, was convicted of five counts: seditious conspiracy, conspiracy to obstruct and official proceeding, obstruction of an official proceeding, conspiracy to impede members of Congress and tampering with documents. During trial, jurors saw communications from Meggs claiming he'd organized an "alliance" between the Oath Keepers and two other right-wing groups: the Florida 3%ers and Proud Boys

"We have decided to work together and shut this s*** down," Meggs wrote in a Dec. 19, 2020, message to other members of the militia.

The jury acquitted Meggs of one count of destruction of government property for tens of thousands of dollars' worth of damage done to the Columbus Doors on the east side of the Capitol. Though two groups of Oath Keepers entered through the doors into the Rotunda, prosecutors failed to show they played any direct role in damaging them.

As to the remaining defendants, jurors found varying levels of culpability and planning.

Harrelson, who reported to Meggs as the Florida Oath Keepers' ground team lead on Jan. 6 and entered the building with him, was convicted of obstruction of an official proceeding, conspiracy to impede members of Congress and tampering with documents. He was acquitted of seditious conspiracy, conspiracy to obstruct an official proceeding and destruction of government property.

Watkins, an Ohio militia leader who entered the building and narrated her time inside on a live Zello chat, was visibly relieved when the "not guilty" verdict was read on the count of seditious conspiracy against her. During the trial, she testified about her painful separation from the military due in large part to her identity as a trans woman and about her lingering desire to serve her country. But, jurors found she did conspire both to obstruct the official proceeding and to impede members of Congress on Jan. 6. She was also convicted of actually obstructing the joint session of Congress and of impeding police during civil disorder, which she admitted to on the stand.

Caldwell, a Berryville, Virginia, resident who served for nearly two decades in the Navy and for a short stint with the FBI, claimed throughout the trial he was not a member of the Oath Keepers and had not been part of any conspiracy. Jurors saw messages he sent seeking a boat for the militia's armed quick reaction force but ultimately acquitted him on all conspiracy counts. He was found guilty of obstruction of an official proceeding and tampering with documents for deleting 180 Facebook messages shortly after he learned of the arrest of Watkins and another defendant, Donovan Crowl.

Although three of the five defendants were acquitted of seditious conspiracy, they will all face a similar starting point in sentencing calculations because obstruction of an official proceeding — the count on which they were all convicted — shares a base offense level with seditious conspiracy. A plea agreement filed in March for Oath Keeper Joshua James, who admitted to both seditious conspiracy and obstruction of an official proceeding, does give some idea of what enhancements prosecutors could seek for the sedition charge and what a potential sentencing range could look like. Before factoring in credit for accepting responsibility, James was facing a recommended sentencing guideline of 10-12.5 years in prison. While James was not ultimately called as a witness in the case, he was expected to receive significant consideration from prosecutors at sentencing for his cooperation.

In other obstruction cases, prosecutors have argued a guideline range of 87-108 months (or 7.25-9 years) was appropriate. In August, the Justice Department requested 96 months in prison for Thomas Robertson, a former Virginia police officer convicted of obstruction of an official proceeding and civil disorder. He was ultimately sentenced to 87 months, and is currently appealing to the D.C. Circuit.

The five defendants who appeared in court Tuesday were among nearly a dozen named in an indictment in January alleging seditious conspiracy — a rarely used charge which alleges a plot to use force to oppose or overthrow the government or prevent or delay the execution of a law of the United States. The trial, which began Oct. 3, was the first prosecution of a seditious conspiracy case in the U.S. since the Justice Department failed to win convictions for several members of the Hutaree militia movement in Michigan in 2010. The Justice Department succeeded in a 1995 case of convicting Sheik Omar Abdel-Rahman, also known as "The Blind Sheik," and nine co-defendants of seditious conspiracy for plotting to bomb military installations, the United Nations, the George Washington Bridge and FBI housing.

The indictment alleged Rhodes rallied his followers after former President Donald Trump’s defeat in the 2020 election in an effort to overturn the results. He urged Trump to activate the military and militia to prevent President Joe Biden from taking office, and told his followers if Trump failed to do so they would have to take matters into their own hands in a “much more desperate, much more bloody war.”

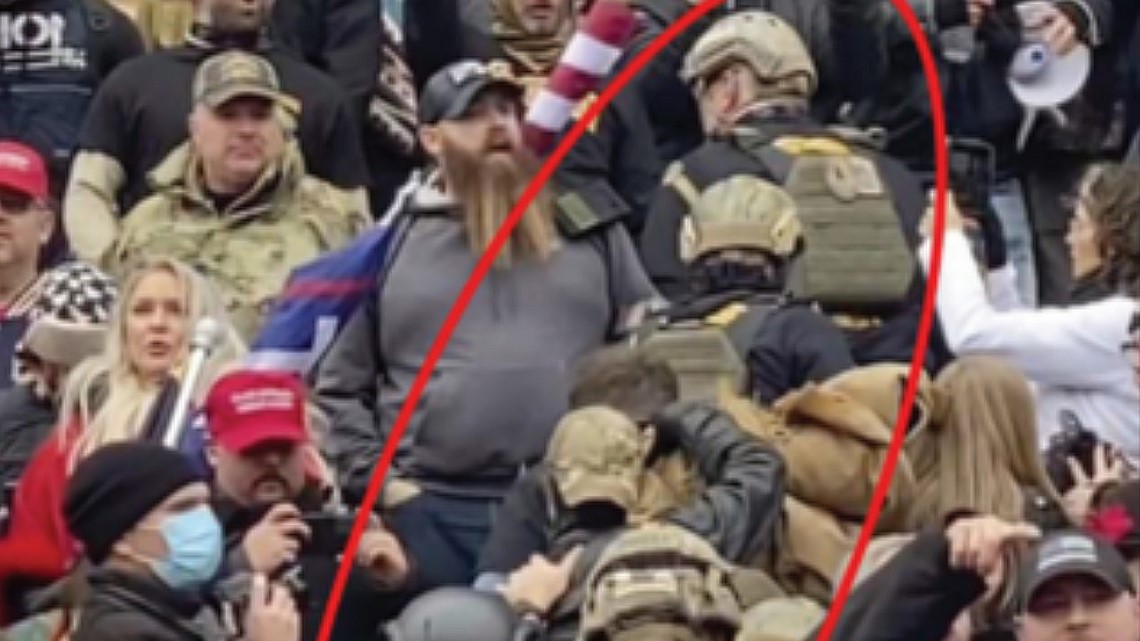

On Jan. 6, 2021, dozens of Oath Keepers from around the country answered Rhodes’ call and traveled to Washington, D.C. Outside the city, the group amassed guns at a Virginia hotel, with some discussing the possibility of acquiring a boat to quickly transport them across the Potomac River. After the Capitol was breached, two separate groups of Oath Keepers entered the building, including Meggs, Harrelson and Watkins.

“These defendants concocted a plan for an armed rebellion to shatter a bedrock of American democracy,” Assistant U.S. Attorney Jeffrey Nestler told jurors during the trial. “They banded together to do whatever was necessary, up to and including force, to stop the transfer of power from President Donald Trump to President-Elect Joe Biden on Jan. 6, 2021.”

Defense attorneys argued Rhodes’ many public and private statements amounted to nothing more than “heated rhetoric,” and said the government could not show a concrete plan to stop the certification of power or use the guns they brought to Northern Virginia for any illicit purpose. In Caldwell’s case, he argued he was never a member of the Oath Keepers to begin with and did not join the group on Jan. 6. The remaining defendants said they came to D.C. to participate in private security details for VIPs at planned Stop the Steal events.

But, a jury saw things differently, finding the weeks of discussions, the interstate transport of guns and the decision to enter the Capitol did amount to an unlawful conspiracy on Rhodes' and Meggs' part to prevent the constitutionally mandated transfer of presidential power.

The verdict will likely bolster the confidence of the Justice Department as it begins two more seditious conspiracy trials in the coming weeks. Jury selection for a second group of Oath Keepers was set to begin Monday before U.S. District Judge Amit P. Mehta, who also oversaw Rhodes’ trial. On Dec. 12, former Proud Boys chairman Enrique Tarrio and four other members of the group were set to begin their own trial in a separate seditious conspiracy case.

Sentencing dates were not set for any of the defendants, but they were expected to come in early spring. Mehta granted a request from Caldwell's attorney to allow him to remain on pretrial release while he awaits sentencing.

‘A General Overlooking a Battlefield’

The government’s theory of the case rested heavily on its portrayal of Rhodes as both the instigating and unifying force of the alleged plot. Over the course of the trial, jurors saw hundreds of messages, open letters and recorded speeches by the militia leader that were full of revolutionary fervor and often spoke of a coming civil war.

During a GoToMeeting with his followers, just days after the November 2020 election was called for President Joe Biden, Rhodes exhorted Oath Keepers to prepare for a fight.

“Let’s make no illusion about what’s going on in this country,” Rhodes said. “We’re very much in exactly the same spot that the founding fathers were in like March 1775. Now – and Patrick Henry was right. Nothing left but to fight. And that’s true for us, too. We’re not getting out of this without a fight.”

Rhodes, a Yale-educated lawyer who was disbarred by the Montana Supreme Court in 2015, testified during trial he believed the 2020 election was unconstitutional and any inauguration of Biden as president would be illegitimate. To prevent that, he promoted a radical plan for former President Donald Trump to invoke the Insurrection Act – a 19th-century law that allows the president to mobilize the military and militia to suppress civil disorder or rebellion – as a means of seizing voting machines across the country and obtaining a “data dump” he believed would show massive fraud.

In both open letters to Trump and numerous messages to his followers, Rhodes said he believed the Insurrection Act would allow the former president to use the Oath Keepers and other military veterans as an auxiliary force to prevent what he described as a “ChiCom” (Chinese Communist) plot to install Biden as president.

As early as the Nov. 9, 2020, GoToMeeting, Rhodes was discussing the Oath Keepers stationing an armed quick reaction force (QRF) just outside of D.C. during events he saw as opportunities for the act to be invoked, including the, at that time, upcoming Million MAGA March on Nov. 14, 2020, and the Jericho March on Dec. 12, 2020, both in D.C. The Oath Keepers also stationed a QRF at the Comfort Inn Ballston on Jan. 6, 2021, although – despite evidence showing him communicating about plans for the QRF – Rhodes denied on the stand having any knowledge of that plan.

But prosecutors alleged Rhodes’ talk of the Insurrection Act was merely a cover for his real motive: an armed conflict to prevent Biden from becoming president. Assistant U.S. Attorney Jeffrey Nestler argued Rhodes saw the obscure law as providing “plausible deniability” for the Oath Keepers’ preparations – something, he told jurors, Rhodes alluded to himself during the Nov. 9 meeting when he told followers their public position was that the QRF was simply waiting for Trump’s orders.

“And the reason why we have to do it that way is because that is your legal cover,” Rhodes said.

By Jan. 6, after months of almost apocalyptic warnings about the incoming Biden presidency, prosecutors argued Rhodes had primed his followers to enter the U.S. Capitol Building at his signal. They argued during the trial he provided that signal in two ways. The first was directly during a three-way call with Michael “Whip” Greene, the Oath Keepers’ operations leader on Jan. 6, and Kelly Meggs, the militia’s Florida state leader. Minutes after that call – which the Oath Keepers denied was able to connect – Meggs led a dozen militia members into the Capitol, including co-defendants Harrelson and Watkins. Caldwell did not enter the building but did join other rioters who reached the restricted Lower West Terrace where the inaugural stage was being built.

Prosecutors said the second signal came via the encrypted Signal app, which Rhodes used to express his support, they said, for the rioters attempting to breach the building.

“All I see Trump doing is complaining. I see no attempt by him to do anything,” Rhodes wrote. “So the patriots are taking it in their own hands. They’ve had enough.”

“When you told the people on this chat that all the president was doing was complaining, that’s all the call you needed to give, isn’t that correct?” Assistant U.S. Attorney Kathryn Rakoczy asked Rhodes during cross-examination.

When Rhodes denied he’d intended that as a call to action, Rakoczy followed up.

“You said next comes our Lexington, isn’t that correct?” she asked.

“That’s what I wrote,” Rhodes acknowledged.

Although more than a dozen Oath Keepers entered the Capitol on Jan. 6, none have been charged, to date, with bringing firearms into the District of Columbia. Prosecutors argued that was because Rhodes didn’t want followers to be arrested and, therefore, unavailable to join in the continuing conspiracy.

As one of the final pieces of evidence in the government’s case, jurors heard a recording of Rhodes made in a Dallas parking lot on Jan. 10, 2021, in which he tried one last time to pass a message to Trump about the Insurrection Act through a man named Jason Alpers – a military special operations veteran who claimed to have contacts close to the former president.

During the recorded conversation, Rhodes expressed his regret that Oath Keepers didn’t bring their rifles to the Capitol and warned that if Trump didn’t take the actions he recommended his family could be jailed and killed by the incoming administration. Alpers, who was called as a witness by the government, testified that he was shocked by what he viewed as violent and extremist rhetoric from Rhodes. In the recording, Alpers can be heard telling Rhodes point-blank that he didn’t want a civil war. Rhodes replied, “Well, you’re gonna have it bud.”

“There’s gonna be combat here on U.S. soil no matter what,” Rhodes said. “No matter what you think they’ll do. It’s coming. No way out it without fighting – you can’t get out of this. It’s too f---ing late.”

Defense Asks: Where’s the Plan?

The five defendants on trial each offered their own argument to the jury. Rhodes spoke of the Insurrection Act. Meggs said he was in D.C. to serve on legitimate private security details. Caldwell, who did not enter the Capitol, argued he was never a member of the Oath Keepers at all and the FBI botched its investigation into him from the get-go. But, one argument served as a unifying theme for all five: the lack of a concrete, written plan for Jan. 6.

Jonathan Crisp, attorney for Watkins, told jurors during his closing remarks the government had spent the previous month “manipulating and deceiving you” into seeing a conspiracy that never materialized.

“What was the plan?” Crisp asked. “'It was implied.' How?”

Attorney Brad Geyer, representing Harrelson, argued the government had shown an “indifference to the truth.” David Fischer, attorney for Caldwell, accused the DOJ from day one of a “bait and switch.” James Lee Bright, one of three attorneys representing Rhodes, offered perhaps the bluntest defense assessment of the government’s case.

“If, for the first time in 209 years, the Capitol is breached and you don’t take the opportunity to call in your QRF?” Bright said. “You’re either the Keystone Cops of insurrectionists, or there’s no insurrection. There’s no in-between on this.”

Bright argued all the messages and speeches jurors had heard from Rhodes – even ones calling for “bloody revolution” and talking about his desire to ‘hang f---in’ Pelosi from a lamppost” – were nothing but rhetoric.

“Horribly heated rhetoric,” Bright said. “Bombast. Inappropriate. But that is not indicative of an agreement – of a meeting of the minds.”

Despite coming through thousands of Signal, Facebook and text messages and hundreds of hours of recordings from before, during and after Jan. 6, no FBI agent was able to get on the stand during trial and point to a concrete, written plan to enter the Capitol or delay the certification of the 2020 election – and defense attorneys repeatedly hammered the government’s witnesses on that fact.

“Isn’t it true you haven’t come across one single, solitary witness who has claimed Thomas Caldwell had a plan to attack the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6?” Fischer asked Special Agent Michael Palian, one of the lead investigators on the case.

“We have not come across a person that has told us that, correct,” Palian said.

During the government’s case, prosecutors argued it wasn’t unusual in a conspiracy not to have a written plan and called former Oath Keepers to testify about what they understood the agreement to be.

Mike Adams, who served for a time as the Oath Keepers’ Florida state leader before Meggs took over the position, said he left the group in late 2020 over the “unchained rhetoric” coming from Rhodes and other militia members.

“[Rhodes’] letters indicated that if the current president, Mr. Trump at the time, did not declare the Insurrection Act and call up the militias and stand this down – if he didn’t do that then we would have to,” Adams testified. “And I was concerned about who that ‘we’ was. I’m not part of that ‘we.’”

Prosecutors also called two Florida Oath Keepers who entered the Capitol on Jan. 6 and later pleaded guilty to felony charges: Jason Dolan and Graydon Young. Young testified that he had become disillusioned with the organization and was preparing not to come to D.C. until Rhodes sent the channel a message on Christmas Day promising action.

“[Trump] needs to know that if he fails to act, then we will,” Rhodes wrote. “He needs to understand that we will have no choice.”

Young, an 11-year veteran of the U.S. Navy Reserves, described entering the Capitol as a Bastille-type moment for him and testified he believed the militia’s plan to stop the transfer of presidential power was “self-evident.” That was a point Dolan, a 19-year veteran of the U.S. Marine Corps, made as well.

Dolan, who pleaded guilty last year to conspiracy and obstruction of an official proceeding, said he believed there was a common understanding that if Trump did not invoke the Insurrection Act then the Oath Keepers would act to stop the certification of the election. On direct examination, Nestler asked Dolan how he believed the militia would do that.

“By any means necessary,” Dolan said. “That’s why we brought our firearms.”

But, not all of the Oath Keepers the government called to the stand agreed with that assessment. Terry Cummings, a Florida member of the militia who traveled to D.C. with Dolan and Harrelson, said he never heard any discussion about entering the Capitol or stopping the certification.

“At any point in the entire day, did you ever hear any human being associated with the Oath Keepers discuss a plan of any sort in regard to the activities you saw that day?” Bright asked him on cross-examination. Cummings said he did not.

Only one defendant among the five admitted any wrongdoing at all: Watkins. In surprise testimony near the end of the trial, the Ohio resident and U.S. Army veteran said she thought the mob entering the Capitol was a “cool, American moment” until they wound up in a confrontation with police. Watkins admitted to being angry about the results of the election and to interfering with officers who were trying to clear the building – effectively an admission to the felony civil disorder charge she faced – but denied any role in or knowledge of a plan to stop the certification on Jan. 6.

We're tracking all of the arrests, charges and investigations into the January 6 assault on the Capitol. Sign up for our Capitol Breach Newsletter here so that you never miss an update.