TOLEDO, Ohio — In August of 1998, the Toledo Police Department’s tip line got a call from a woman claiming to be Shondrea Rayford. The woman said she had information on the killing of a 13-year-old boy in central Toledo on June 15.

It was a brutal killing, and the woman said that her boyfriend, Travis Slaughter, admitted to it.

Slaughter would later confess to police his role in the killing, but he also implicated two other men, Karl Willis and Wayne Braddy, in the killing.

Willis and Braddy have maintained their innocence for nearly 20 years and numerous issues discovered by 11 Investigates raise serious questions about the case. Slaughter received a significantly reduced sentence for the killing and an unrelated rape in exchange for his testimony against Braddy and Willis. He has since recanted that testimony and said that the men had nothing to do with the killing.

But, deeper questions surround Rayford. A grand jury initially declined to indict Braddy and Willis after their arrest on Aug. 27, 1999. Nine months later, they were indicted, and the lead prosecutor in the case, Andy Lastra, told 11 Investigates in July that Rayford was the key in getting that indictment. He said Rayford told police that Slaughter told her that Braddy and Willis were involved and that she overheard a conversation between the men about the killing.

But now, Rayford is telling a much different story. During an interview Thursday morning, she said that she never knew anything about the killing. Then, she leveled serious accusations against Lastra and police.

“It was a story I knew nothing about, a story that the detectives made up. I never knew anything about the case until the detectives came up with the story. And then I was supposed to get on the stand and say something about something I didn’t know nothing about,” she said.

She was subpoenaed to testify in the January of 2000 trial. After answering basic questions, Rayford suddenly quit responding. The judge then held her in contempt of court and sent her to the county jail for 30 days. Rayford was 19 years old, was working multiple jobs, and had no criminal record until that point.

In July, jury foreman Jon Crye told 11 Investigates that the jury assumed that Rayford stopped testifying because she was afraid of Braddy and Willis. He said it was a key moment for the panel, which still took 26 hours to find the men guilty.

She says fear of Braddy and Willis had nothing to do with it. She said she didn’t even know the men and had nothing bad to say about them.

“I knew nothing they wanted me to know,” Rayford said of why she stopped testifying. “They wanted me to go up there and say something I knew nothing about.”

When asked if she was afraid of lying on the stand and perjuring herself, she said, “That’s what they wanted me to do, yes.”

Police spokesperson Kevan Toney offered the following statement in response:

“Her accusations are highly suspect since they come 20 years after the fact,” Toney said. “There is no evidence that anything she alleges is based in truth.”

Jeffrey Lingo from the prosecutor’s office responded with PDFs of recent appellate decisions denying Braddy and Willis new trials. But appellate courts always require “new evidence.” It assumes that whatever Rayford and Slaughter say now, they knew at the time of trial, so their statements cannot be considered new evidence. But there were nearly 150 exonerations in the United States last year, and many of those exonerations came after court appeals had been exhausted. At that point, prosecutors need to step in. Last year, Richard Phillips was released from prison after 47 years when the Wayne County conviction integrity unit reviewed the case and determined there were many concerns about the police investigation.

Rayford’s handling by police and prosecutors was unusual from the start. Detective notes and Rayford’s testimony noted that she was involved in meetings between police, prosecutors, and Slaughter. It is typical for witnesses to be interviewed separately so there can be no inference that there is collusion on a story, though courts have consistently given police wide latitude in how they conduct an investigation.

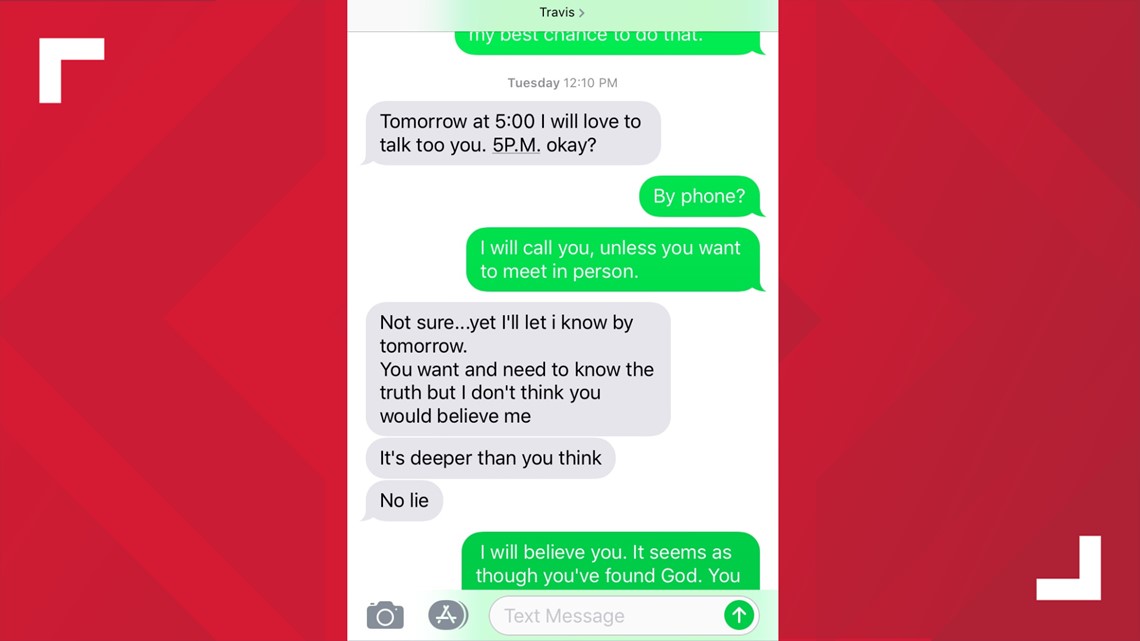

At this point, Rayford and Slaughter have both said that Braddy and Willis had nothing to do with the killing. There are no witnesses saying they were involved, though both men are still serving sentences of at least 23 years. In fact, Slaughter, who was released in 2016, reached out to 11 Investigates from a number identified as his. His intent was to set up an interview, saying there is much more to the story.

In those texts, Slaughter said, “You want and need to know the truth, but I don’t think you would believe me. It’s deeper than you think – no lie.”

At a later point, his parole officer told him that he could not give an interview, and additional texts were not returned.

11 Investigates then took the information to Lucas County Prosecutor Julia Bates, telling her that Slaughter was willing to talk. She replied with a simple “thank you,” and there has been no follow-up.

It has now been 30 days since Bates was approached about sitting down for an interview to discuss not only the case, but also the possibility of the county starting a conviction integrity unit to increase the public’s confidence in the court system. She has refused to meet.

But there are now deeper questions surrounding the prosecutor’s handling of this case. After attempts to get the office’s Braddy and Willis case files were ignored for five weeks, WTOL retained a lawyer to demand the public documents.

Documents were then turned over, but a review of the boxes of files could find none of the original files. The only thing turned over were documents related to multiple appeals. When pressed on the issue, assistant prosecutor John Borell said there were no more documents.

The office then supplied a records retention schedule after a request. In that document, it says that criminal case files are to be kept “Permanently.” (See page 3.)

University of Toledo law professor Gregory M. Gilchrist was asked about the missing files.

“It’s extremely concerning. I struggle to see how they are handling appeals without those original files,” Gilchrist said.

In July, 11 Investigates tried to get the Aug. 27, 1998, videotaped interrogation of Slaughter. There was a key 12-minute period in a detective’s report where Slaughter changed his story and implicated Braddy and Willis. At trial, the defense was told that the conversation with detectives was all on videotape. Those tapes can no longer be found. The police and prosecutor have said they cannot locate them.

At this point, the hopes of Braddy and Willis likely rest with Bates. But since being elected in 1996, there are no listed cases on the National Registry of Exonerations in which Bates willingly reopened the case.

It is a case that has destroyed multiple lives, and has tormented Rayford for nearly 20 years.

“My name was drug through the mud, and so was Karl and Wayne’s. And they are trying to say it is off something I knew or said, and it’s all false,” she said.

There have now been more than 9.1 million views of 11 Investigates’ August 14 report, “Guilty Without Proof.”